By Sarah Nason

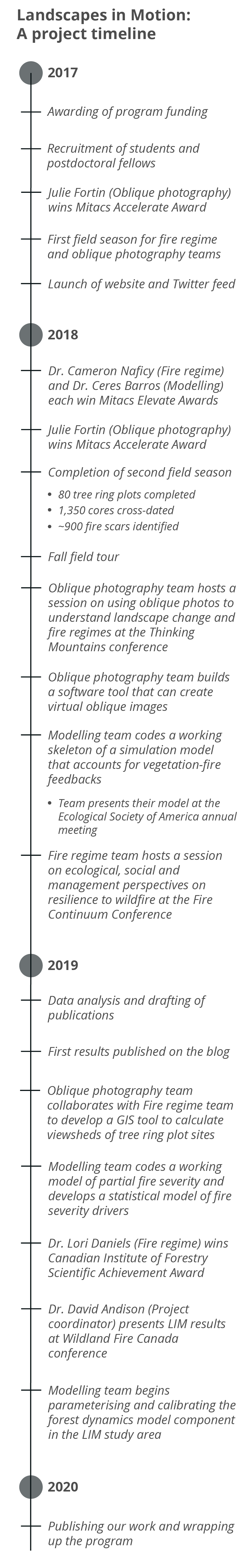

Two years and countless hours of field, lab, and computer study by three diverse research teams have added up to new insights on the fire history of Alberta’s Southern Rockies. One of the key findings of the Landscapes in Motion research program to-date is that fire regimes in the Southern Rockies are complex, including low-severity burns and historical influences of fire suppression and Indigenous cultural burning. In this post, project coordinator Dr. David Andison and fire regime team lead Dr. Lori Daniels share what the implications of these findings might be, what questions remain to be answered, and where our work is going next.

Bringing together three teams of researchers that use different methods might not seem like the most straightforward way to set up a research program. But diversity leads to insight: with the power of collaboration, a world of research possibilities can open up. At the start of the Landscapes in Motion (LIM) program, there was a sense of both excitement and healthy realism among our researchers. As our fire regime team lead Dr. Lori Daniels puts it, we knew we needed to make sure that the different research methodologies would “mesh rather than clash” with one another.

Now at the two-year mark for our program, it is safe to say the multi-disciplinary nature of LIM has been one of the program’s greatest strengths. By working together, our teams have been able to deliver a unique product that would have been unthinkable before we collaborated.

“We’ve been able to put together a truly integrated team that brings together multiple lines of evidence to understand how the foothills landscape historically functioned,” says Daniels. “The on-the-ground research teams [have] embraced the broader vision of LIM and run with it. They’ve taken the project beyond what even we had envisioned.”

So, having taken advantage of the variety of perspectives and expertise of our three teams – what have we learned so far?

Fire regimes in the Southern Rockies of Alberta are diverse

Through our research teams’ examination of historical photos and tree rings, we have found that a mix of fire regimes were present in the forests of the Southern Rockies. These regimes included low- and moderate-severity burns, challenging previous assumptions about how these systems work.

“The boreal and mountain forests of the foothills are still called a stand-replacing ecosystem, and it’s still taught that way in fire courses and in ecology – the prevalent idea being that all the fires are very hot and they burn most of the vegetation,” says LIM project coordinator Dr. David Andison. “I think we’ve pretty much determined that’s not the case.”

Low-severity burns, while less eye-catching than raging crown fires, serve an important purpose in many ecosystems. As a vital part of mixed-severity fire regimes, these burns can help to naturally regulate fuel loads and reduce the risk of out-of-control fires in the future. As well, the practice of using low-severity controlled burns is embedded in many Indigenous cultures as a way to manage fire risk, open up animal habitat, stimulate plant growth, and thaw soils in spring, among other uses.

“The fires that make it onto the news are the big bad ones – but that’s not most fires,” explains Andison. “The ones that are small don’t make the news, but there are lots of small fires out there, and historically, those ones were very important for biodiversity and health of the forest.”

In both the past and present, these low-severity fires are more likely to be successfully extinguished than high-severity fires. These fires are therefore often suppressed before providing their vital contributions to the forest.

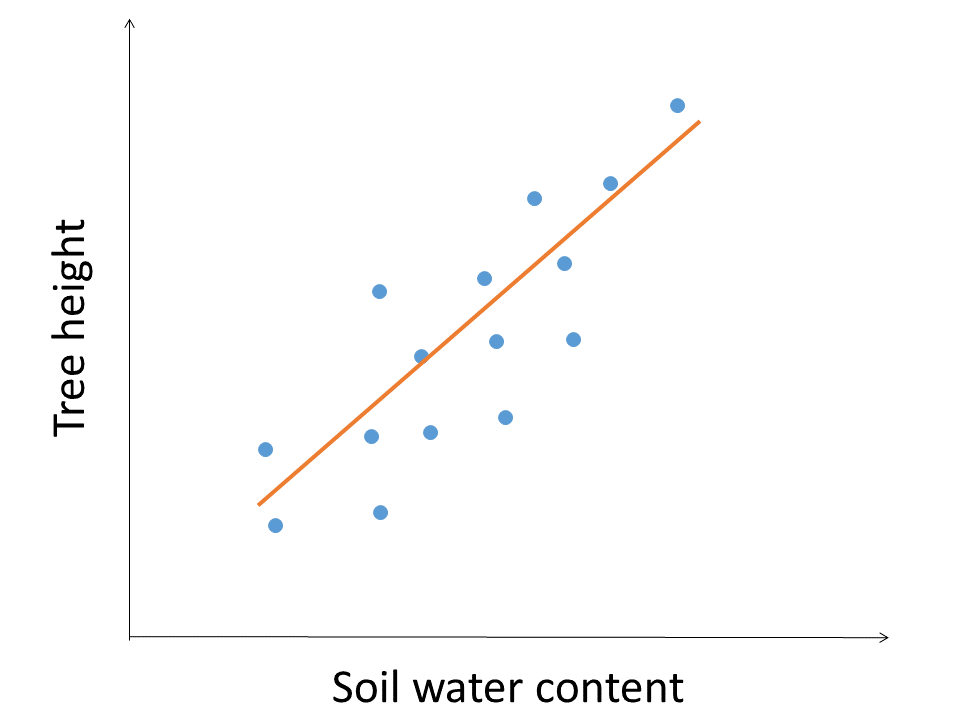

By comparing tree ring data with historical photos, our research team has also found that the presence of fires at a range of severities produced patchy, diverse landscapes. Stands were differently aged and composed of different species depending on the timing and severity of the last burn.

Approaches to the management of forests in Alberta have historically been based on the principle that most fires are high-severity and stand-replacing. The findings of the LIM program suggest that these management techniques, such as fire suppression and exclusion of Indigenous cultural burning, have produced a different landscape from what existed historically in the Southern Rockies region.

“When we look at the landscape today, it appears very uniform or homogeneous. There is less diversity today than in historical photos and indicated by the tree ring data. The lack of surface fires, in absence of Indigenous cultural burning, and the putting out of all lightning-ignited fires, have important implications for how we manage the forest and fires today,” says Daniels.

Multiple possibilities for managing Alberta’s forests

Our team’s research has clearly shown that the landscapes of the Southern Rockies have changed over the last century. Those changes have made landscapes more uniform and vulnerable to high-severity fires. The question of what ought to be valued, conserved, or changed about these landscapes in the future is another discussion – and one that the LIM program’s data and analyses can contribute to.

“There’s a lot of different ways that mother nature can be,” says Andison. “It’s still our choice of what landscapes we want to have and what we want for the future. This project is not about having right or wrong ways about having landscapes. When we think about our future, we should be upfront about evaluating the risks of all our options.”

The LIM program will continue to provide information to help people assess those risks. For example, as fire risk continues to increase globally as a result of climate change[1], this information can help forest managers and community leaders decide how to respond.

“We need to open our eyes wide and take a close look to see how we can adapt,” says Daniels. “We can learn from other parts of the world. For example, Australia is currently experiencing fires at a scale they’ve never experienced before, with huge implications for ecosystems and communities.”

Based on the data collected by the LIM fire regime team, the LIM modeling team will soon be working to predict future scenarios for the forests of the Southern Rockies. These analyses will include climate change scenarios, which can help support land managers and decision-makers to understand and manage risks.

Both our research and the work of others show that wildfires can be unpredictable and often impossible to control. But this does not mean that research can’t help communities understand their risks and take action to adapt to environmental changes. It is therefore important for researchers, forest managers, and community members to collaboratively discuss how communities can safely coexist with future wildfires.

What’s next for Landscapes in Motion?

One of our team’s main priorities going forward is to continue to pursue and grow dialogues about fire management with the communities and stakeholders in our study area. This includes sharing information with local First Nations, environmental non-governmental organizations, the forest industry, and governments to support decision-making and discussion related to community-level risk management.

“We know from our work that there have been significant changes to tree density and continuity of the forest, increasing fuel loads that potentially put communities and citizens at risk,” says Daniels. “We can work with organizations that are trying to make good science-based decisions.”

Our team also hopes to host another community-based event similar to the field tour that took place near the beginning of the LIM program. Information on this type of event will be made available here and on our twitter feed as plans are confirmed.

When it comes to data analysis and research, our work is not yet done! Our diligent modeling team is currently working on fitting together several pieces of the LIM puzzle. Watch our blog for updates and to learn about the results of this work, including:

- Modeling partial mortality: what happens to the landscape when some trees survive after a burn? (part one)

- Scenario modeling: what might happen to landscapes in the future under climate change?

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.

[1] Jones, M.W., Smith, A., Betts, R., Canadell, J.G., Prentice, I.C., and Le Quéré, C. (2020). Climate change increases the risk of wildfires. ScienceBrief Review. Retrieved 15 January 2020 from https://sciencebrief.org/briefs/wildfires.