Ben Williamson

Disturbance is perilous to caribou. It is more than just the absence of the old, deep forests full of lichen that caribou need, and more even than the disconnection of the remaining patches of good habitat. Because disturbance is not an empty absence of plants and animals. It is habitat of a different kind, favouring different species. And some of these species eat caribou.

Throughout Alberta caribou ranges, there are many kinds of disturbance. Roads, cutblocks, pipelines, and well pads abound; seismic lines are among the most pervasive. When forest stands are harvested, the area inside the cutblocks are replanted and the old trees are replaced with young trees, which will, in time, become old trees again. But in the shadow of the untouched trees, at the edges of cutblocks and roads, they are not replanted with seedlings. Instead, a new understory flourishes in this edge micro-climate.The edge is more exposed to sun, rain, and wind, and the soil may be heavily compacted by the machinery that made the feature.

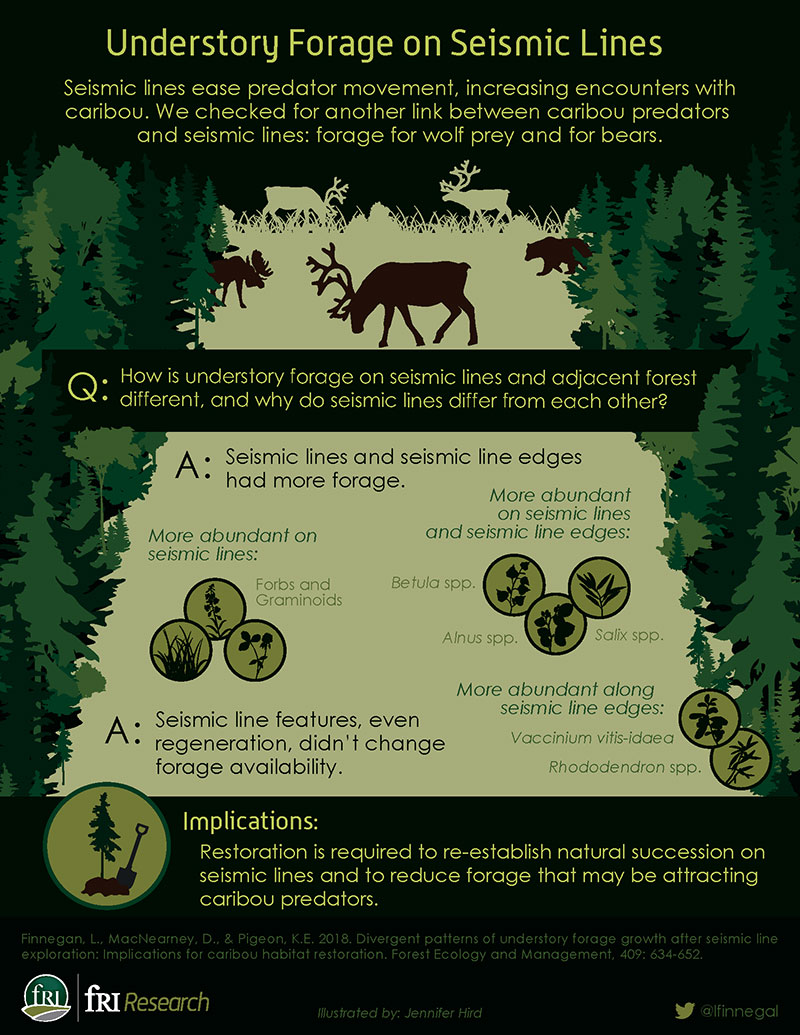

A new Caribou Program paper has confirmed that this is the case also for seismic lines. Like the other disturbance edges, natural succession seems to stall out on many of them, and decades after their creation they show little sign of regrowing to resemble the surrounding forest.

The legacy seismic lines cut before the 1990s are 5–8 metres wide, to accommodate the equipment that they used to discover oil and gas deposits. It isn’t uncommon to find 10 km of seismic lines criss-crossing a single square kilometer of boreal forest.

Field crews were dispatched to 351 of these seismic lines in caribou ranges to see what was growing on them, at their edges, and a stone’s throw into the adjacent forest. This forest is mainly pine, spruce, and poplar, though in wet lowland areas there is more larch and muskeg. But step from the trees onto a seismic line, and the story is quite different. Even on lines over 40 years old, you find things like clover, grasses, willow, alder, and birch.

These species all love disturbance, and are loved, in turn, by the likes of moose and bears who may amble leisurely up the straight, easy path of a seismic line, munching away a lazy afternoon. And in the case of moose, the food chain has another link. They draw other predators besides the foraging bear: wolves and cougars also take an interest in areas where they are likely to encounter ungulates.

All of this spells trouble for caribou. Their patches of old growth forest have been sliced and diced, and the edges are not merely areas without food and cover, but may be actively attracting prey and their predators. And what’s more, it seems these features are surprisingly permanent, a steady source danger for decades.

To provide enough habitat for the Alberta herds to survive, these seismic lines must return to old forest, but it is now clear that they will not do so on their own. It seems necessary to take some active steps to set them on the right trajectory, as people do for the interior of cutblocks and other reclaimed industrial areas. Replanted, the seismic lines may gradually fade, regeneration can fuse forest fragments into larger and larger sections, and the long odds facing caribou in Alberta may improve.