By Alina C. Fisher & Sonia Voicescu

[This post originally appeared on the Mountain Legacy Project website on Feb. 21, 2020. You can check out the MLP blog here.]

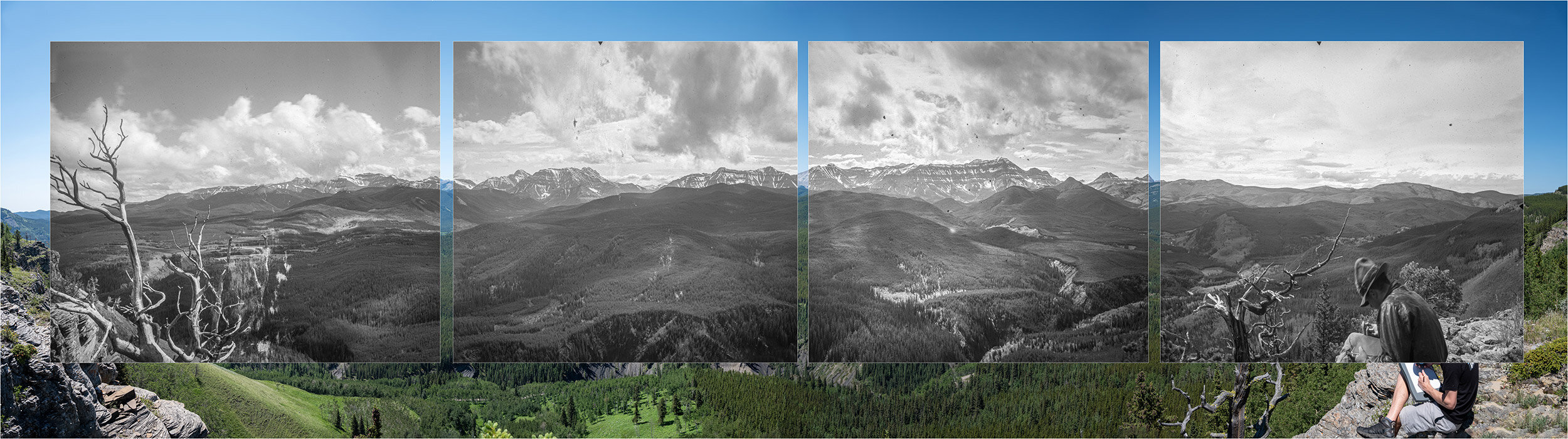

The Repeat Photography Team relies on historical photographs to determine which mountains to visit in the field, and compare them with modern photos to analyze how the landscape has changed since surveyors last stood there. But where do those historical photographs come from? Alina Fisher and Sonia Voicescu traveled to Library and Archives Canada in early February to explore and digitize thousands of historical photographs, and they’ve shared their time travel experience.

Several weeks ago, we got to experience time travel. It wasn’t the thing of movies, where we sat in a time machine, amongst flashing colours and futuristic noises, which brought us to a stunning landscape we had never seen before. Rather, this time portal was one of glass plate negatives, light tables, and computer screens. It was much less the grandeur of Hollywood, and more the quiet wonderment of stepping into an old and mysterious library, keeper of knowledge from a previous era.

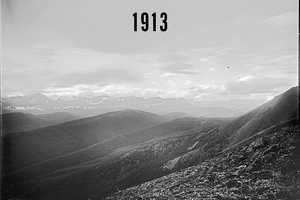

You may wonder what brought us to experience such a voyage. As part of research undertaken for the Mountain Legacy Project (MLP), we work in partnership with Library and Archives Canada (LAC) to digitize thousands of glass plate negatives taken by some of the first Dominion Land surveyors in Canada. As part of the overarching colonial apparatus, the surveyors were tasked with mapping our country starting in the 1880s, long before it encompassed the whole of Canada as we know it today. To map the more challenging terrain of the Rocky Mountains, they devised a method that combined photography with complex trigonometry in order to calculate elevations and distances between these high peaks. Their surveys and photos informed the first maps of the Rocky Mountains, its rivers and lakes, and the places where rail lines would eventually be constructed to fuel the country’s westward expansion.

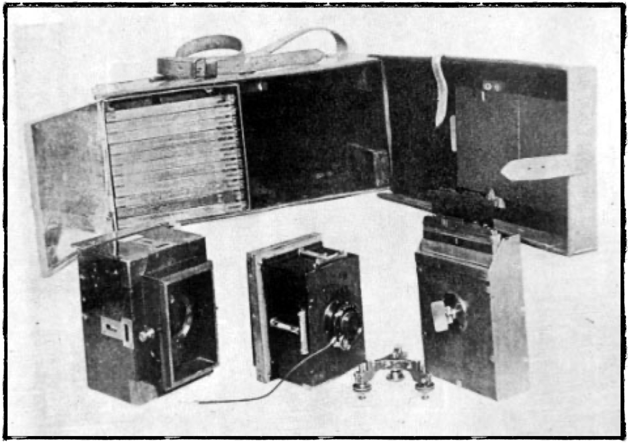

Taking the photographs was not a simple endeavour. It may sound simple enough—follow a path up to a mountain top and snap a photo—after all, thousands of tourists do it every year throughout the Rockies. However, routes up mountainsides were not well known to those surveyors and had to be tested bit by bit until a suitable, and somewhat safe, trail was found. In those days, cameras were anything but portable in the modern sense. Each photographic negative was taken on a glass plate, using a large accordion box camera that was both bulky and sensitive. Once the photos were taken, they had to be brought back down the mountain, ridden to the nearest rail line by pack horse, and sent back to Calgary or Ottawa via a bumpy train ride. When the photographs reached their destination, the surveyor would use them to create maps of the surveyed region over the winter months.

Once maps were made, the glass plate negatives were stored away in boxes, and most were never seen again… until a group of intrepid researchers—Eric Higgs, Jeanine Rhemtulla, and Ian MacLaren—uncovered them some 100 years later. These researchers were some of the very first members of the Mountain Legacy Project, and the uncovering of this amazing collection has led to some outstanding research and publications. Twenty years have passed since this discovery, during which time the image collection was restored and curated by a team of dedicated archivists and specialists in photo conservation from Library and Archives Canada (shout out to Jill Delaney, Kayley Kimball, and the other talented LAC archivists and curators!). The photographs are now housed at Library and Archives Canada’s Preservation Centre in Gatineau, QC, in temperature-controlled and sealed vaults. It is this collection, and these vaults, that enabled our voyage through time.

Seeing the mountain images from over a hundred years ago was a form of time travel in itself! To see the extent of glaciers barely visible today, glance at grasslands and meadows prior to fire suppression and treeline creep, see evidence of Indigenous land management practices, and peek at images of early farmsteads eking out a livelihood in an unknown land is an experience not encountered by many. It was also humbling to see and handle the delicate glass plate negatives themselves. Some had cracked or disintegrated with time. Some fell prey to the degradation of the sensitive emulsion, and some were marked with the fingerprint of someone that last handled them before they were filed away for an unknown length of time.

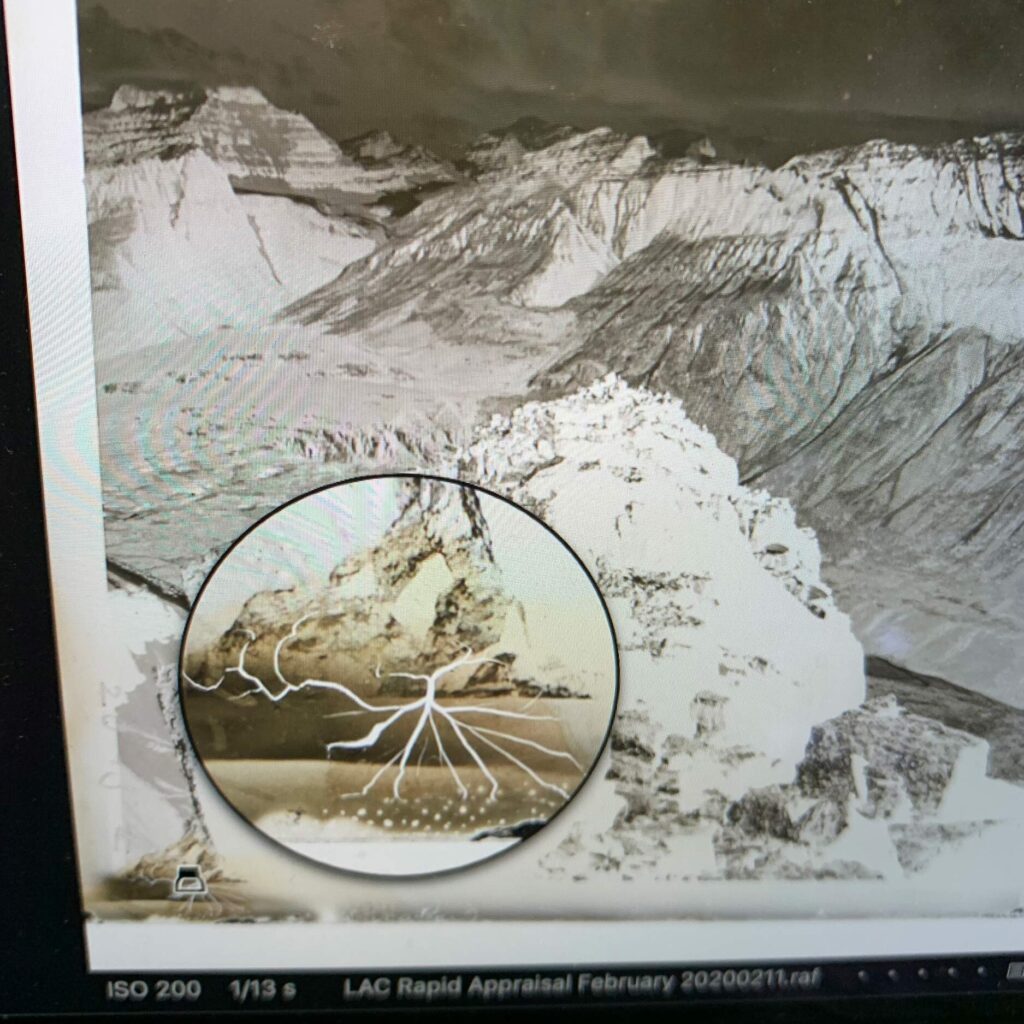

The 5,000 glass plate negatives that we got to see on this trip are but a mere drop in the bucket of what is housed at Library and Archives Canada—the entire collection is estimated to be close to 120,000 images. To digitize these images, our research team performs what we call a “rapid appraisal” technique: we remove each negative from its protective envelope, carefully place it on top of a light table, and photograph it. Within a day, we can capture approximately 1,000 images of these negatives, which then need to be turned into positives (i.e inverted) and sometimes enhanced in further post-processing.

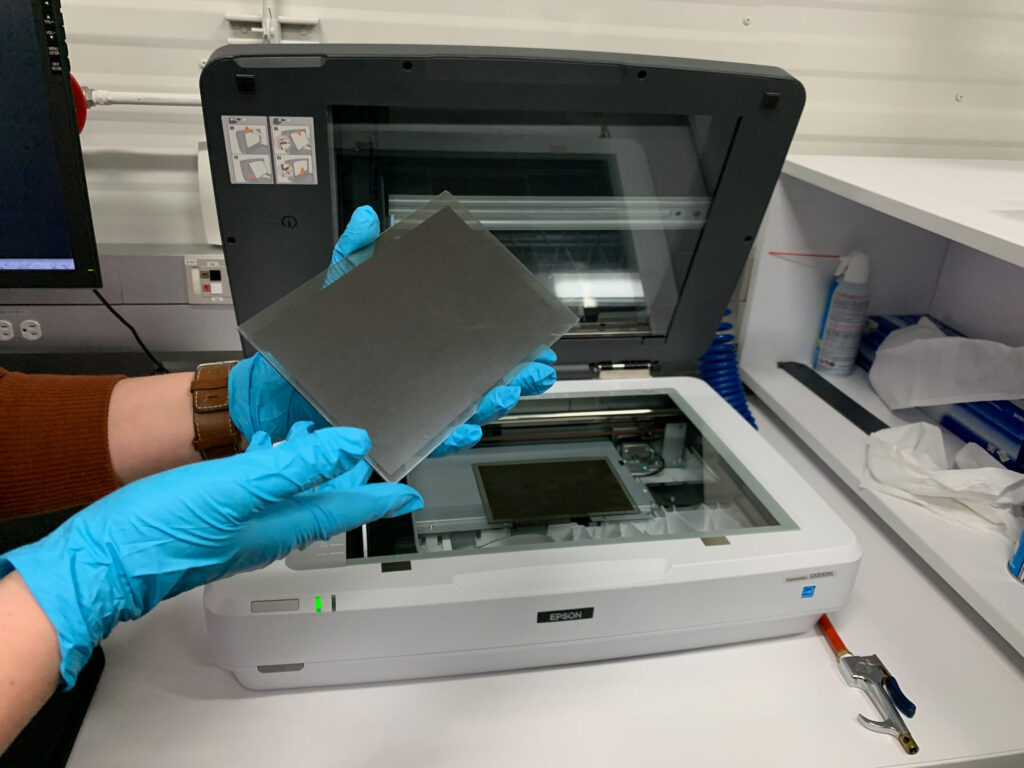

This technique, although very careful and methodical as to not damage plates, can only generate low-quality images at best. For the MLP, this image quality is sufficient for planning fieldwork and deciding what mountain peaks to climb in search of modern-day views. However, for our research and analysis purposes, we need to obtain high-resolution scans of the repeated images. This involves the detailed work of digital archival specialists from Library and Archives Canada, who are able to scan the plates through a high-resolution scanner. These specialists can scan approximately 50 plates within a day, so high-resolution scans for this most recent visit could, for example, take up to 100 days to complete.

As we reflect upon this most recent visit to Library and Archives Canada, we feel honoured to be part of the team of researchers and surveyors that came before us, and in forwarding the research of the Mountain Legacy Project. One day, our photos may help others to look at changing landscapes in the centuries ahead.

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.