By Sonya Odsen

Imagine you are standing on a mountain peak in the Rockies. You’re out of breath from climbing for hours to reach this point, with a magnificent view as the reward for your efforts. In fact, you snap a few photos.

Now ask yourself: what if, 100 years from now, someone had to use those photos to try and find this exact spot, within a single metre. Do you think they could do it?

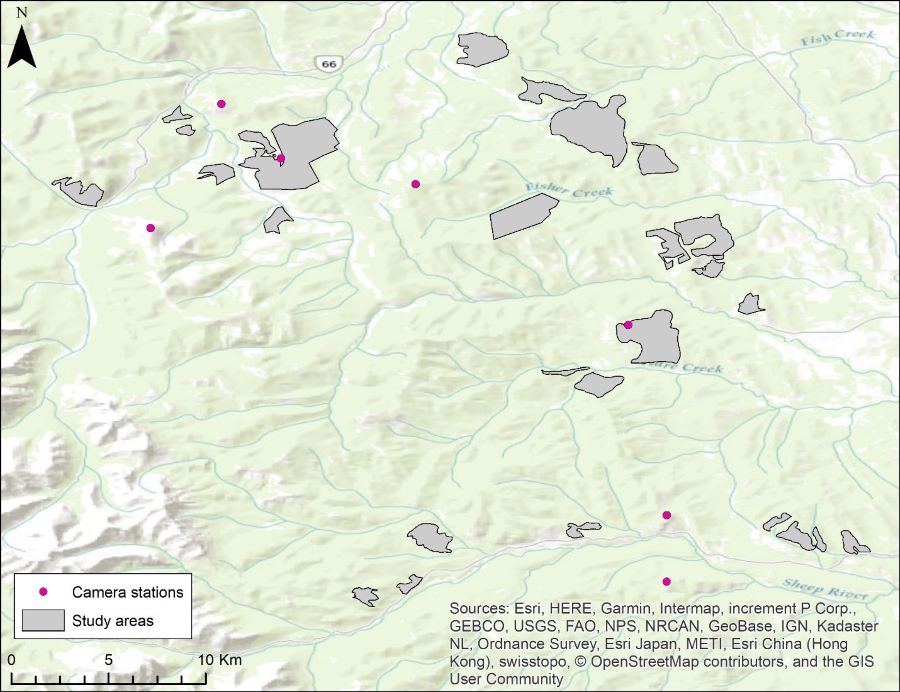

Turns out, that’s exactly what researchers with the Mountain Legacy Project, which includes Eric Higgs and Julie Fortin of Landscapes in Motion’s Oblique Photography team, do every summer. These modern-day explorers are locating the exact spots where surveyors once stood, and they recapture matching images of the landscape with remarkable precision—providing a critical tool for comparing past and present landscapes.

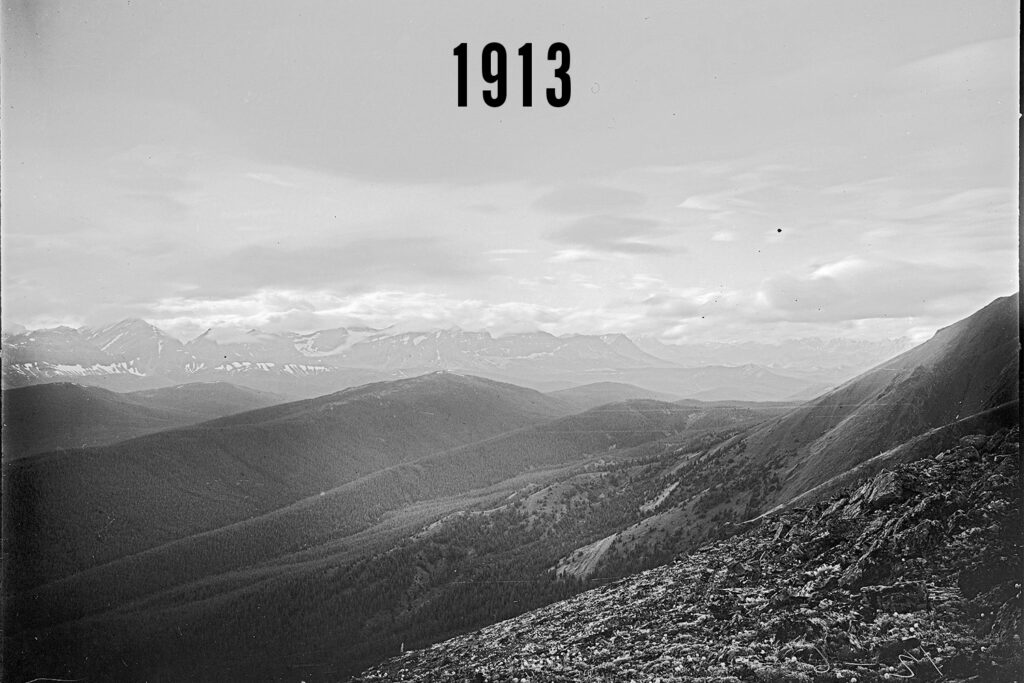

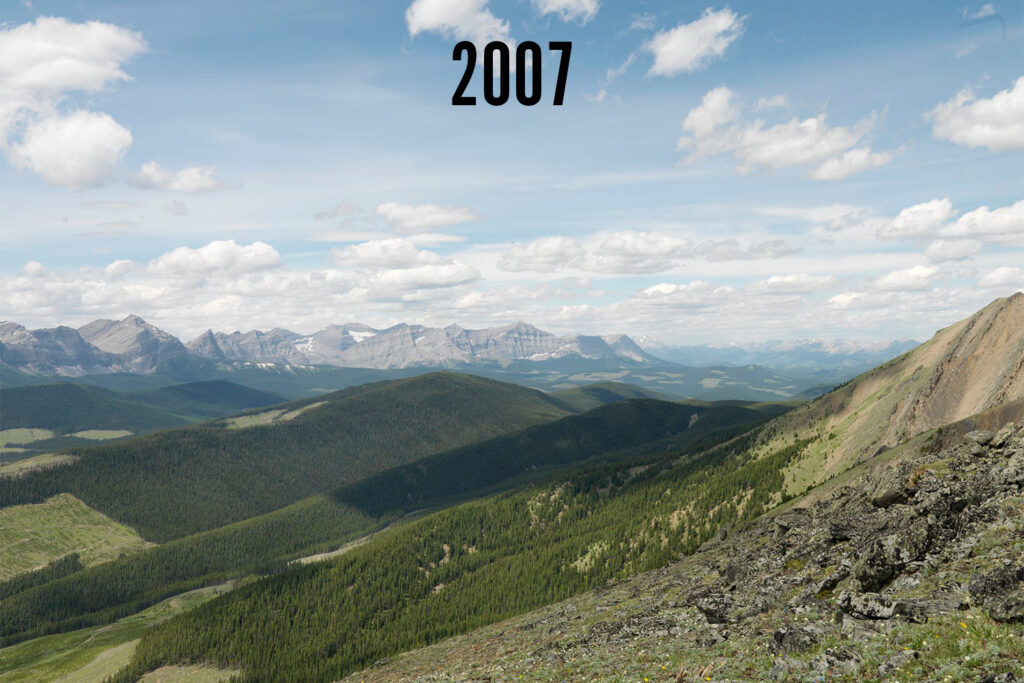

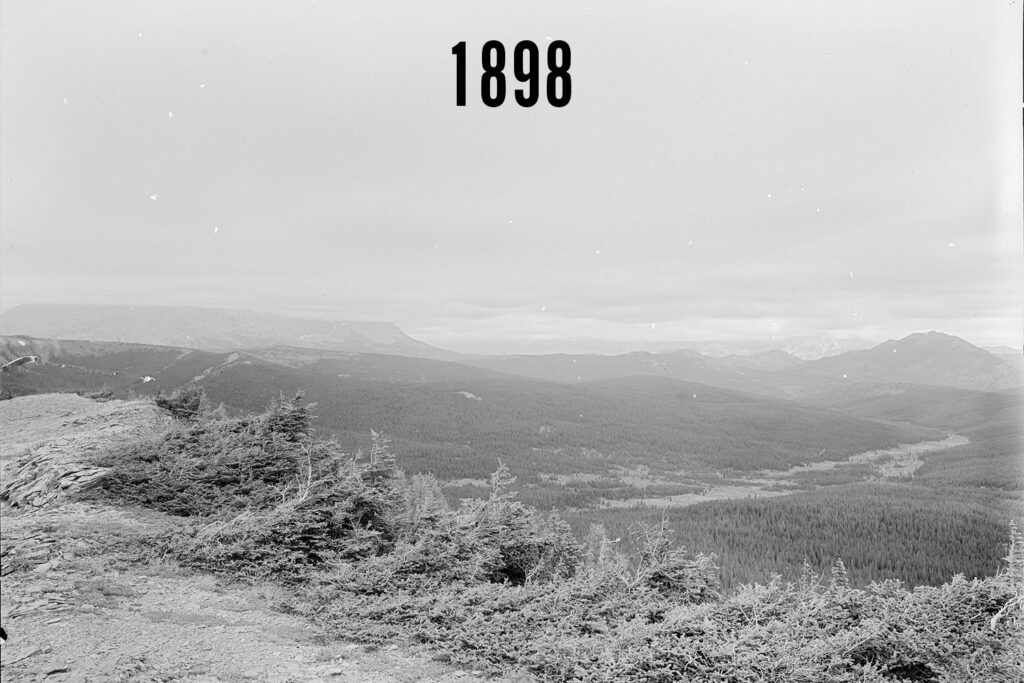

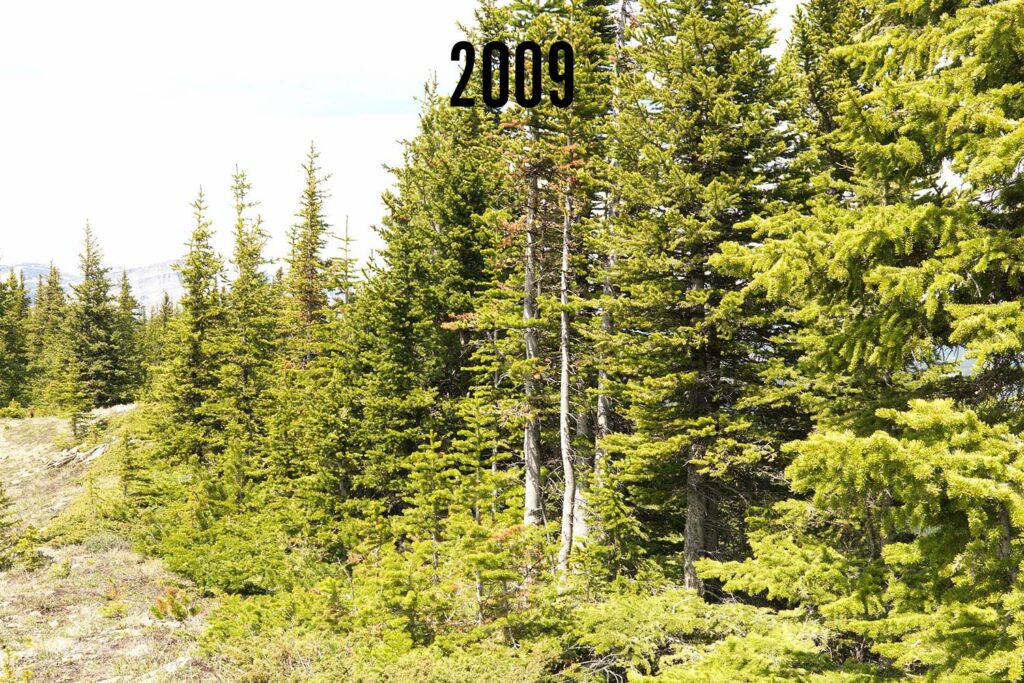

Repeat photographs of these landscapes, such as these photos taken on Pasque Mountain, allow researchers to analyze the ways landscapes have changed. This includes natural phenomena like treelines going higher up the mountain and human footprints like cutblocks. Photos by the Mountain Legacy Project.

But first: how did surveyors do it?

In the mid to late 1800s, surveyors mapping western Canada used some of the first portable cameras to photograph the landscapes they surveyed. These photos were used to create topographic maps—maps showing changes in elevation from hills to valleys and more.

These cameras may have been “portable,” but not really by today’s standards. The combined weight of the camera, tripod, glass plate negatives and other accessories could be more than 9 kg (or 20 pounds, about as much as a car tire). Because of these hefty cameras, crews were usually made up of several men to help the surveyor transport his gear, prepare food, and pack and unpack campsites. And of course, they traveled by horseback—motorized helicopters were not invented until the turn of the 20th century and would not be capable of long-distance travel until World War II.

Surveyors hiked up to mountain peaks, set up their camera on a tripod, and photographed the surrounding mountains. Sometimes they could do this from a single location, and sometimes they would need to move the tripod to different locations to capture their entire surroundings.

Sometimes, they would build a stone cairn to mark the location, which has come in very handy about a century later.

Finding the original location

Fast-forward to the 21st century. Beginning under the name “Bridgland Repeat Photography Project” in 1998 out of the University of Alberta, the project grew, moved to the University of Victoria, and eventually received the name “Mountain Legacy Project”. As of 2016, the project had taken over 7,000 repeat photographs.

So how on earth do they figure out the exact location where a surveyor stood up to a hundred years earlier?

One of the early steps to determine the location might surprise you: they eyeball it in Google Earth. They zoom into the general area where the surveyor was known to be working the year the photo was taken, then look for the mountain profiles that are visible in the image. Using this process, researchers are actually able to narrow it down to the mountain peak where a photo was taken, and punch that into a GPS for the field crew.

Once the field crew makes it to the mountain peak, they use a printed copy of the historical photograph and explore the peak until they find the location where the scene in front of them matches the scene in the image. If the surveyor left a stone cairn, this process is pretty straightforward—in all likelihood, a camera set up immediately next to or even on the cairn will line up perfectly. If they didn’t, it can be a lot trickier.

Sometimes, factors like new tree growth can block the view, making it nearly impossible to capture an image that matches the historical photograph exactly. Photos courtesy of the Mountain Legacy Project.

In some cases, the original location of the historical photograph is not accessible. This might be because the soil where the tripod was placed has eroded away, or the glacier it stood on has since receded. There might also be new vegetation that blocks the view of the landscape, or even buildings when photographing more developed areas. In these cases, it is simply not possible to capture an exact match, so researchers get the best image they can.

This may sound like a highly inaccurate process, but it’s shockingly effective. In most cases, researchers get within less than a metre of the original location from which the historical photograph was taken!

This 1948 photograph was recaptured in 2016 on the south side of Mist Mountain. It is still pending alignment using software. Photos courtesy of the Mountain Legacy Project.

Important considerations

There are many additional elements researchers need to consider when recapturing historical photographs. When it comes to repeat photography, attention to detail is key.

As much as possible, researchers try and take photographs at the same time of year, the same time of day, and under the same air quality conditions as the historical photograph they are trying to match.

Of course, getting all of these conditions to line up is not possible in most cases. For one thing, not all of the historical photographs include a date or time. And even if they do, it may not be logistically feasible to match each photo to the original date, time, and conditions as the original photograph during a short field season with a long list of peaks to climb. All it takes is rain, fog, smoke, or helicopters being unavailable to throw off the best-planned schedule.

Only the beginning

The work done by researchers to replicate historical photographs in the field is critical, but it is not the only step used to match up modern and historical images. Once the field season is over, researchers begin processing the images to line things up even better. They use special software to align images as closely as possible and analyse them, and this process will be explored in greater detail in a future blog post.

These images are proving critical in helping scientists and managers better understand disturbance regimes in the southern Rockies of Alberta. Stay tuned for more blog posts about have the data is being used in the Landscapes in Motion Project.

Want to learn more about the nitty-gritty of capturing repeat photographs? Check out the Mountain Legacy Project Guidebook that Julie Fortin prepared as a handy resource for new crew members.

Sonya Odsen is an Ecologist and Science Communicator with a background in boreal ecology and conservation. She is a regular writer for Landscapes in Motion and is part of the Outreach and Engagement Team for the project.

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.