By Julie Fortin

[This post also appears on the Mountain Legacy Project website. You can check out the MLP blog here.]

As the Oblique Photography team prepares to head out into the field, they are training new field staff how to find the locations where land surveyors once stood to photograph the landscape. Sometimes it’s a bit more complicated (see our last blog post!), but sometimes there is a nice, friendly marker left behind by surveyors of the past…

Have you ever come across a pile of stones carefully perched atop one another while hiking in the Rockies? If so, there is a chance that you walked by a cairn that was built by land surveyors over 100 years ago.

Markers put to new use

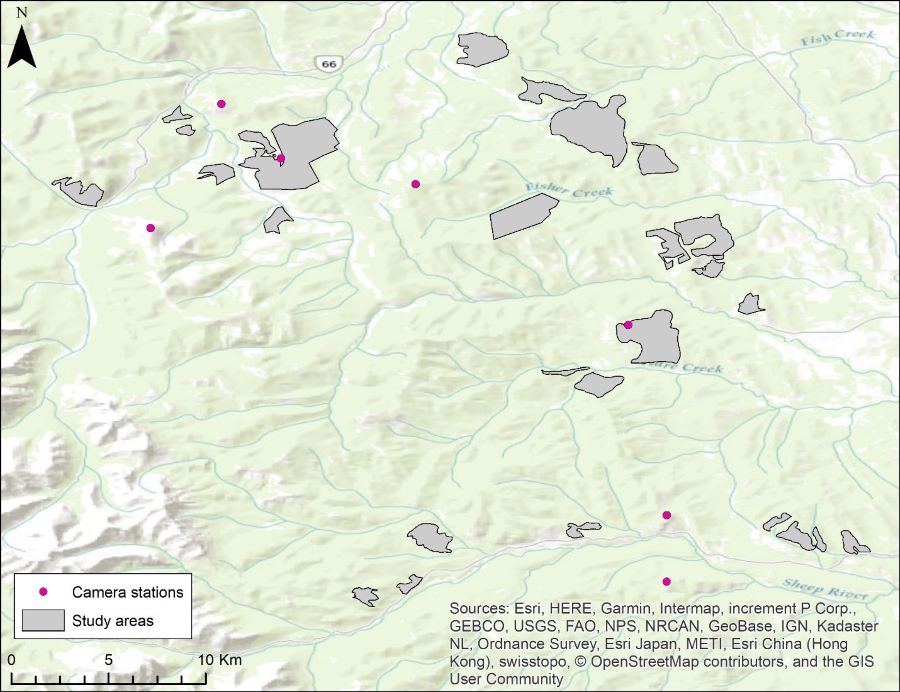

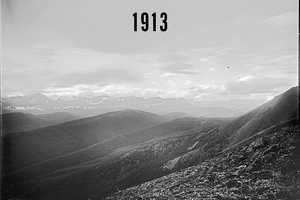

At the turn of the 20th century, various government bureaus hired surveyors to map out the mountains of western Canada. These engineers used unique “photo-topographic” survey methods: they took pictures systematically from mountain peaks and then used special tools to create topographic maps based on the photographs. For the maps to be accurate, each part of the landscape needed to be captured in at least two different photographs and it was crucial to measure the angle between those photos. In order to do this precisely, the location from which photos were taken needed to be marked in a way that was visible in other photographs taken from kilometres away. The surveyors’ solution was to build large cairns, 4 to 6 feet tall, exactly where they had positioned the camera. The cairns would thus be visible from other camera stations, which would allow for precise angle measurements from the photos.

Keen eyes are an asset when searching for cairns on distant peaks. The image on the left is the cairn located at Bridgland Station 355 (near the Kootenay Plains), and the image in the centre is the same cairn, photographed from Station 356. (Or it might be Julie—hard to say at this resolution!). Photos and map courtesy Julie Fortin and the Mountain Legacy Project.

This is a gross oversimplification of the complicated field and office methods involved in phototopographic surveying – for an in-depth explanation, see Morrison Parsons Bridgland’s 1924 work, “Photographic surveying”. Nevertheless, it explains why there are large piles of stones on many mountains in the Canadian Rockies. And this is helpful to the researchers of the Mountain Legacy Project (MLP). The objective of MLP field crews being to take repeat photographs from the exact same position as the historical photos, large physical markers indicating “the photos were taken from here!” come in especially handy.

Left: Julie Fortin takes a photo from her position next to a cairn built by surveyors. Right: Sandra Frey and Navarana Smith line up next to a different cairn. Photos courtesy Julie Fortin.

At the mercy of nature (and people!)

In the intervening time between the surveyors building the cairn and MLP researchers returning to it, many things could have happened: sometimes rodents adopt the pile of rocks as a lookout perch (we often see an orange lichen, Xanthoria elegans, that is associated with animal urine), sometimes wasps choose to build nests within it, and sometimes hikers leave message bottles inside. But what the MLP generally hopes is that a) the cairn was not destroyed (be it by weather, animals or hikers), and that b) they haven’t been following a false trail around a “decoy” cairn that was not actually built by the early surveyors. Indeed, often tourists and hikers build cairns in celebration of their successful summit, but these can confuse MLP researchers and others seeking true, historically important markers.

The cairns are not only at the mercy of the elements—sometimes MLP researchers themselves have to interfere with them. Despite the advantages for field crews, sometimes large cairns can get in the way of the view, forcing repeat photographers to partially dismantle (and later reassemble!) the cairn or to move their camera around the cairn to complete their panoramas.

Can you find one?

So the next time you come across a 6-foot cairn in the Rockies, visit explore.mountainlegacy.ca to see whether a surveyor took photos there 100 years ago. But please, don’t take the cairn apart!

Julie Fortin is a Master’s student with the Mountain Legacy Project, and a member of the Oblique Photography Team with Landscapes in Motion.

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.