Note: Operations within Spotted Owl range may be recommended to discourage Barred Owl occupancy, rather than promoting it. See Spotted Owl.

Barred Owl

(Strix varia)

Habitat Ecology

- Barred owls are associated with large trees and snags in old (>80 years) mixedwood forests and, in BC, upland mature and old conifer forests.1

- Aspen and poplars provide nest trees, while white spruce and balsam fir provide cover for owlets.2

- Structural diversity, including partially fallen trees, is important near nest trees.3

- They also use Douglas fir, western hemlock, western larch, and black cottonwood forests (coniferous or mixed), often near water.4

- Barred Owls mainly nest in large-diameter deciduous trees in natural cavities formed by disease, broken branches, or broken tops. Woodpecker cavities are too small for this large-bodied species. They will readily use nest boxes.1

Response to Forest Management

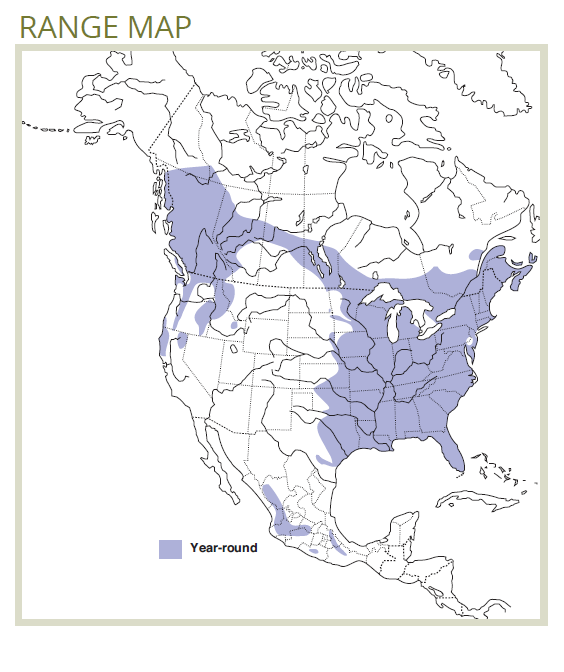

- Barred Owls require large, contiguous mature forest habitat and have been negatively impacted by severe fragmentation and habitat loss in parts of their range.2

- Where the Barred Owl’s range overlaps with that of the Great Horned Owl, fragmentation negatively affects Barred Owls by creating habitat for this aggressive predator and competitor.2

- Clear-cutting without retention is considered an important threat due to loss of cavity trees and snags for nesting.1

- Barred owls have been observed nesting in retention patches and within 50 m of cutblock edges in landscapes with a low amount of harvested area (7%).5

Stand-level Recommendations

- Managers should prioritize old (>100 years), large-diameter (>36 cm) deciduous trees and snags as anchor points for retention patches, particularly those with large existing cavities, and/or broken tops.6 If these are scarce or unavailable, some large deciduous trees may be retained to provide future nest trees. Unmerchantable timber should be retained near large retention trees, including spruce or fir if available, to provide cover for owlets.2,3

- Patch retention more effectively provides nesting habitats within harvest sites for this species, while dispersed retention trees provide hunting perches for Barred Owl and other species while the harvest block regenerates.7

- Patches should be 10–20 ha or larger if possible, and contain high densities of large-diameter aspen and poplar trees/snags for nesting.5

- Recommended activity buffers around known, active nests range from 50 m (low-impact activities) to 200 m (high-impact activities, e.g., road building). An unharvested forest patch of at least 20 m radius is recommended around the nest tree.8

Landscape-level Recommendations

- The most benefit for Barred Owls will likely be derived from large stands of mixedwood forest >100 years.2 The size, amount, and composition of these stands should be determined within the context of the natural range of variation for the region.9

- Retention harvesting (patches) may be effective on landscapes with low disturbance intensity, but patches may have less value on intensely-managed landscapes. In these cases, large stands of unharvested forest are likely more effective. Patches offer value by potentially providing nesting structures as the harvested stand regenerates and improving landscape-level complexity,5 and are expected to more quickly produce habitats suitable for Barred Owl than severe fires or clearcuts.10

References

- Mazur, K. M. & James, P. C. 2000. Barred Owl (Strix varia), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.508

- Alberta Sustainable Resource Development. 2005. Status of the barred owl (Strix varia) in Alberta. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, and Alberta Conservation Association, Wildlife Status Report No. 56, Edmonton, AB. 15 pp.

- Alberta Environment and Parks. 2016. Barred Owl Conservation Management Plan 2016-2021. Alberta Environment and Parks. Species at Risk Conservation Management Plan No. 14, Edmonton, AB. 10 pp. Available online: http://aep.alberta.ca/fish-wildlife/species-at-risk/species-at-risk-publ…

- Cannings, R. J. 2015. Barred Owl. in The Atlas of the Breeding Birds of British Columbia, 2008-2012 (Davidson, P. J. A., Cannings, R. J., Couturier, A. R., Lepage, D. & Di Corrado, C. M., eds.) Bird Studies Canada, Delta, B.C. Available online: http://www.birdatlas.bc.ca/accounts/speciesaccount.jsp?sp=BDOW&lang=en

- Olsen, B. T., Hannon, S. J. & Court, G. S. 2006. Short-term response of breeding barred owls to forestry in a boreal mixedwood forest landscape. Avian Conservation and Ecology 1: 1. Available online: http://www.ace-eco.org/vol1/iss3/art1/

- Bonar, R. 2018. Personal communication. April 6, 2018

- Piorecky, M. D. & Prescott, D. R. C. 2004. Distribution, abundance and habitat selection of northern pygmy and barred owls along the eastern slopes of the Alberta Rocky Mountains. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 91, Edmonton, AB. 26 pp.

- OMNR. 2010. Forest Management Guide for Conserving Biodiversity at the Stand and Site Scales – Background and Rationale for Direction. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Toronto, ON. 575 pp.

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 6: Boreal Taiga Plains. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Edmonton, Alberta. 288 pp.

- Bonar, R. 2018. Personal Communication.