This soot-coloured woodpecker hunts for bark and wood-boring beetles in burned and very old coniferous forests. The subtle sound of it flicking bark off trees, or drilling for beetle grubs, announces its presence.

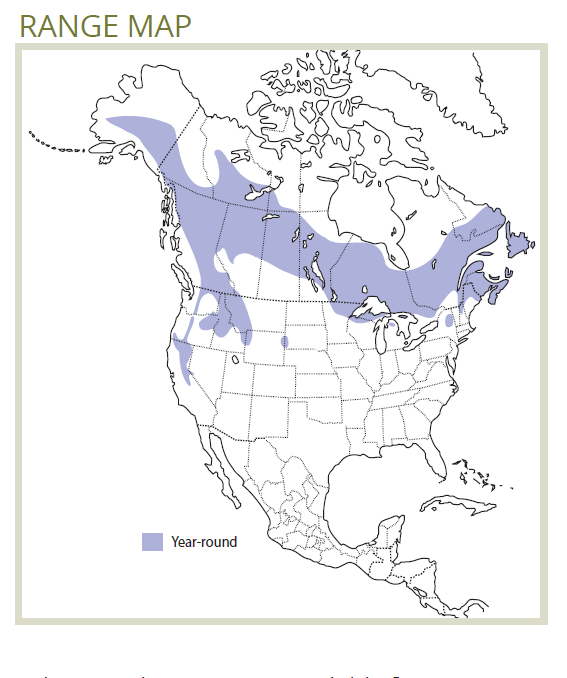

Black-backed Woodpecker

(Picoides arcticus)

Habitat Ecology

- Black-backed Woodpeckers are most common in 2–8 years post-fire conifer-dominated forests that have not been logged or salvaged.1–3

- Forest types include spruce, tamarack, Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, lodgepole pine, and jack pine.4

- They are negatively associated with high densities of deciduous trees.2

- They are most abundant in stands with high densities of smaller-diameter burned conifers (e.g., ≥23 cm dbh in Douglas fir/ponderosa pine5 or 14–19 cm dbh in boreal jack pine/spruce3).

- They excavate nests in large-diameter trees and snags with low decay.1

- Conifer forests >110 years old likely provide important habitat when recently burned forest is not available.3

Response to Forest Management

- Black-backed woodpeckers are strongly negatively affected by postfire salvage logging, which removes both foraging and nesting habitat.4

- Salvage logging of Mountain Pine Beetle-killed stands may also have a negative effect.6

- Within salvage-logged stands, woodpeckers nested in retention patches even when dispersed trees were available.5

- Summer wildfires in coniferous forests create higher-quality foraging habitat than fall/winter prescribed burns or MPB infestations.7

Stand-level Recommendations

- Patch retention during salvage logging of burned forests is strongly recommended:

- Retention patches containing both small-diameter trees for foraging and larger-diameter trees for nesting are recommended. Average recommended densities across the salvaged area are >104–123 trees or snags/ha (>23 cm dbh).5

- Retention recommendations range from trees or snags >23 cm dbh for Black-backed Woodpeckers5, to >40 cm dbh to provide habitat for a range of primary and secondary cavity nesters including Black-backed Woodpeckers.8

- Given the high densities of burned trees/snags preferred by this species, clearcut areas exceeding 2.5 ha are discouraged within salvage areas.4

- Planners should include patches located far from the edges of unburned forest, as unburned forest is a source of nest predators.9 Black spruce-dominated forest is the exception to this recommendation.10

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Recent postfire coniferous forest is the most valuable habitat for Black-backed Woodpeckers. Old coniferous forests (>110 years) at levels derived from NRV analyses should be represented on the landscape to support this species where and when postfire stands <8 years old are unavailable.3

- Old coniferous forests >100 up to >380 ha should be conserved if possible given reported home range sizes in unburned forest.⁴

References

- Saab, V. A., Russell, R. E. & Dudley, J. G. 2007. Nest densities of cavity-nesting birds in relation to postfire salvage logging and time since wildfire. The Condor 109: 97–108. Available online: http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1650/0010-5422(2007)109[97:NDOCBI]2.0.CO;2

- Koivula, M. J. & Schmiegelow, F. K. A. 2007. Boreal woodpecker assemblages in recently burned forested landscapes in Alberta, Canada: Effects of post-fire harvesting and burn severity. Forest Ecology and Management 242: 606–618. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.01.075

- Hoyt, J. S. & Hannon, S. J. 2002. Habitat associations of black-backed and three-toed woodpeckers in the boreal forest of Alberta. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 32: 1881–1888.

- Tremblay, J. A., Dixon, R. D., Saab, V. A., Pyle, P. & Patten, M. A. 2016. Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus), version 3.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.bkbwoo.03

- Saab, V. A. & Dudley, J. G. 1998. Responses of cavity-nesting birds to stand-replacement fire and salvage logging in ponderosa pine/Douglas-fir forests of southwestern Idaho. Research Paper RMRS-RP-11, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogen, UT. 17 pp. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/23853

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 6: Boreal Taiga Plains. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Edmonton, Alberta. 288 pp.

- Rota, C. T., Rumble, M. A., Lehman, C. P., Kesler, D. C. & Millspaugh, J. J. 2015. Apparent foraging success reflects habitat quality in an irruptive species, the Black-backed Woodpecker. The Condor 117: 178–191.

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 9 Pacific and Yukon Region: Great Basin. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Delta, British Columbia. 105 pages + appendices.

- Saab, V. A., Russell, R. E., Rotella, J. & Dudley, J. G. 2011. Modeling nest survival of cavity-nesting birds in relation to postfire salvage logging. Journal of Wildlife Management 75: 794–804.

- Drapeau, P., Nappi, A., Imbeau, L. & Saint-Germain, M. 2009. Standing deadwood for keystone bird species in the eastern boreal forest: Managing for snag dynamics. Forestry Chronicle 85: 227–234.

- Bonar, R. 2018. Personal communication. April 6, 2018