With browner plumage than the black-capped chickadee, the boreal chickadee’s squawking “TISK-a-day” or “FITZ-brew” song is commonly heard in older spruce forests.

Boreal Chickadee

(Poecile hudsonicus)

Habitat Ecology

- Boreal Chickadees are found in conifer forests (mainly spruce and sometimes balsam fir) and mixedwoods. In northern BC, they are found across a range of habitats including open forests.1

- In Alberta, they are found mainly in older (>80 years) forests.2

- In BC spruce-fir forests, they are also found in 31–75 year-old burns containing residual trees.3

- Lowland black spruce or tamarack forest may represent valuable habitat.4

- This species excavates nest cavities in snags with very soft heartwood or reuses cavities excavated by small woodpeckers.1

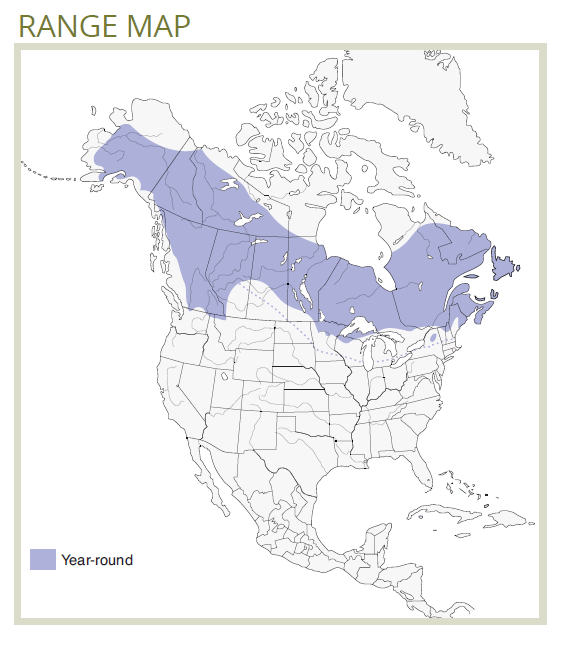

- The Boreal Chickadee is a year-round resident that prefers mature stands in the winter.5

Response to Forest Management

- Boreal Chickadees avoid young and regenerating harvested stands, and they are expected to decline where old conifer forests are reduced (landscape-level) and potential nest trees/snags are removed (stand-level).6,7

- Boreal Chickadees were unlikely to be present in regenerating clearcuts (i.e. no planned retention) up to 33 years postharvest.8

- Some winter use of regenerating stands (4–7 m tall balsam fir/white spruce) has been observed, however chickadees mainly used habitats at edges between cutblocks and mature (>7 m tall) forests.9

- They were more than twice as abundant in un-thinned lodgepole pine stands than stands that were thinned seven years earlier.10

Stand-level Recommendations

- Retention at levels of up to 22% and patches up to 5 ha do not appear to benefit this species in the short term.11,12

- Longer-term benefits of retention include large-diameter residual trees contributing to potential nest trees as they are excavated by woodpeckers or become soft enough for chickadees to excavate.13

- Large-diameter aspen (>35 cm dbh) with conks or other damage, plus large-diameter spruce, are recommended for inclusion in retention patches.

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Boreal Chickadees are not considered sensitive to fragmentation,9 however their absence from patches ≤5 ha in one study suggests larger blocks of older coniferous or mixedwood forest are valuable.12

- Networks of older spruce and/or mixedwood stands will be important for maintaining this species, and near-rotation age spruce and mixed stands may also contribute to habitat on the landscape.

- Old and/or lowland black spruce and tamarack stands may support high densities, suggesting this component of the passive landbase (e.g., wet, unmerchantable, or off-target species) likely contributes to habitat for the Boreal Chickadee.4,14

References

- Ficken, M. S., McLaren, M. A. & Hailman, J. P. 1996. Boreal Chickadee (Poecile hudsonicus), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA.

- Hannon, S. J., Cotterill, S. E. & Schmiegelow, F. K. A. 2004. Identifying rare species of songbirds in managed forests: Application of an ecoregional template to a boreal mixedwood system. Forest Ecology and Management 191: 157–170.

- Schieck, J. & Song, S. J. 2006. Changes in bird communities throughout succession following fire and harvest in boreal forests of western North America: literature review and meta-analyses. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36: 1299–1318. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1139/x06-017

- Zlonis, E. J., Panci, H. G., Bednar, J. D., Hamady, M. & Niemi, G. J. 2017. Habitats and landscapes associated with bird species in a lowland conifer-dominated ecosystem. Avian Conservation & Ecology 12: 7.

- NCASI. 2006. Synthesis of large-scale bird conservation plans in Canada: A resource for forest managers. Special Report No. 06-05. Research Triangle Park, N.C.: National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc.

- Thompson, I. D., Kirk, D. A. & Jastrebski, C. 2013. Does postharvest silviculture improve convergence of avian communities in managed and old-growth boreal forests? Canada Journal of Forest Research 43: 1050–1062. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2013-0104

- Hadley, A. & Desrochers, A. 2008. Response of wintering Boreal Chickadees (Poecile hudsonica) to forest edges: does weather matter? The Auk 125: 30–38. Available online: http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1525/auk.2008.125.1.30

- Leston, L., Bayne, E. & Schmiegelow, F. 2018. Long-term changes in boreal forest occupancy within regenerating harvest units. Forest Ecology and Management 421: 40–53. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.029

- Hadley, A. & Desrochers, A. 2008. Winter habitat use by boreal chickadee flocks in a managed forest. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 120: 139–145.

- Bayne, E. M. & Nielsen, B. 2011. Temporal trends in bird abundance in response to thinning of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta). Canadian Journal of Forest Research 41: 1917–1927. Available online: http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/10.1139/x11-113#.Wftr0NCnFzB

- Mahon, C. L., Steventon, J. D. & Martin, K. 2008. Cavity and bark nesting bird response to partial cutting in northern conifer forests. Forest Ecology and Management 256: 2145–2153. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.08.005

- Lance, A. N. & Phinney, M. 2001. Bird responses to partial retention timber harvesting in central interior British Columbia. Forest Ecology and Management 142: 267–280.

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 4 in Canada: Northwestern Interior Forest. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Whitehorse, Yukon. 138 pp. + appendices.

- ABMI. 2017. Boreal Chickadee (Poecile hudsonicus). ABMI Species Website, version 4.1