This nationally threatened species occupies wet, deciduous-leading forests, where complex understory vegetation and deep leaf litter hide their ground nests.

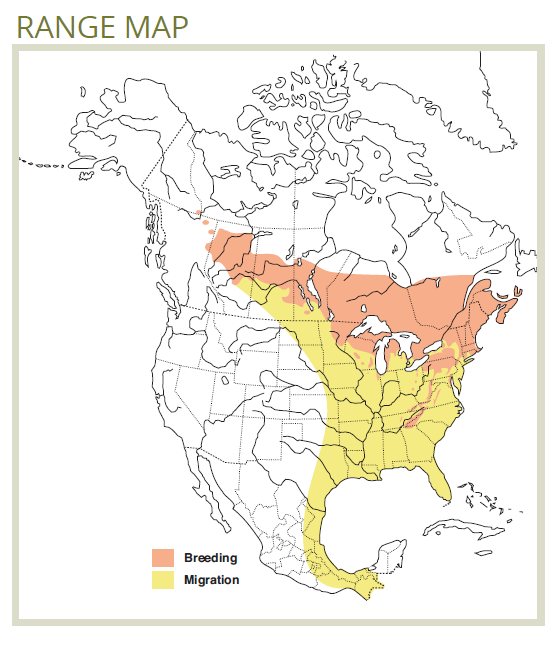

Canada Warbler

(Cardellina canadensis)

Habitat Ecology

- Canada Warbler’s primary habitat is cool, moist, typically deciduous-leading forest with a dense shrub understory, complex ground cover, and steep slopes and/or open water.1

- Forests older than rotation age (e.g., >125 years) are consistently identified as the most valuable habitat for this species, as well as high shrub cover within stands.2,3

- In Alberta, they are strongly associated with deciduous-dominated forest >80 years old and areas near small, incised streams.4

Response to Forest Management

- Canada Warblers have shown some use of young (11–30 years) clearcuts5 and postharvest stands containing large residual trees and brushy block edges.6 However, recent research using province-wide data in Alberta suggests that young forest, regardless of origin, is not suitable habitat for this species.4

- It has been suggested that Canada Warblers are far more likely to use harvest units where there are high densities of Canada Warblers in nearby unharvested forests, and regenerating forest itself may be suboptimal habitat.5,7

- Canada Warblers were essentially absent from stands with low retention (2–6%) immediately after harvest in deciduous forests of Alberta.8

- Canada Warbler abundances have shown a relationship with spruce budworm abundances, suggesting a possible connection to spruce budworm declines in some provinces. Field testing to establish a causal link is strongly recommended.9

Stand-level Recommendations

- Unharvested areas (e.g., Wildlife Habitat Areas in BC) may be appropriate where several pairs are present. These areas should ≥500 m in diameter. Should pairs be located near a stream, these patches should ideally be placed linearly along the slope above the stream.10

- Wide riparian buffers are recommended for at least a portion of a harvested area, including voluntary buffers of ephemeral and intermittent streams. Buffers exceeding the minimum buffer widths required by regulations are recommended within deciduous forests >80 years old with a well-developed shrub layer.4 This variability in buffer widths should also bring harvests more in line with NRV patterns.

- If possible, high retention levels (e.g., 30–50%) paired with shrub and understory protection are recommended in high-quality occupied habitats where harvesting cannot be avoided.3,11,12

- Stand tending that suppresses shrub growth will negatively affect habitat quality.3 Similarly, selection harvesting within dense old stands with suppressed shrub growth may be beneficial by promoting shrub growth.1

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Old deciduous-leading forest on the landscape is the most important habitat for this species, and the highest-quality habitat areas (old, wet forest with dense shrub layer) should be prioritized for set-asides or extended rotations. Stands with breeding pairs (e.g., pre-harvest surveys and/or habitat models) should be a very high priority for protection, as Canada Warblers are more likely to establish territories near other members of their species.4,7,13

- Minimum old forest stand sizes of 100 ha are recommended,14 however the amount of habitat is considered more important than continuity based on Canada Warbler’s relative tolerance of fragmentation (i.e., reserves not meeting the 100 ha target still have value).4,15 NRV analyses may also serve as a useful guide for establishing patch sizes on the landscape.

- Deciduous forests 11–30 years old and containing some overstory residual trees may represent secondary or sub-optimal habitat on the landscape, but their value is questionable.2

Knowledge Gaps

- While this species has been observed using stands <80 years old, reproductive studies are necessary to determine whether pairs are successfully reproducing in these habitats.

References

- Reitsma, L., Goodnow, M., Hallworth, M. T. & Conway, C. J. 2009. Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.421

- Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development and Alberta Conservation Association. 2014. Status of the Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis) in Alberta. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development. Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 70, Edmonton, AB. 41 pp.

- Environment Canada. 2015. Recovery Strategy for Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vi + 55 pp.

- Ball, J. R. et al. 2016. Regional habitat needs of a nationally listed species, Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis), in Alberta. Avian Conservation and Ecology 11: 10. Available online: http://www.ace-eco.org/vol11/iss2/art10/

- Leston, L., Bayne, E. & Schmiegelow, F. 2018. Long-term changes in boreal forest occupancy within regenerating harvest units. Forest Ecology and Management 421: 40–53. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.029

- Schieck, J. & Song, S. J. 2006. Changes in bird communities throughout succession following fire and harvest in boreal forests of western North America: literature review and meta-analyses. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36: 1299–1318. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1139/x06-017

- Hunt, A. R., Bayne, E. M. & Haché, S. 2017. Forestry and conspecifics influence Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis) habitat use and reproductive activity in boreal Alberta, Canada. The Condor 119: 832–847. Available online: http://www.bioone.org/doi/10.1650/CONDOR-17-35.1

- Schieck, J., Stuart-Smith, K. & Norton, M. 2000. Bird communities are affected by amount and dispersion of vegetation retained in mixedwood boreal forest harvest areas. Forest Ecology and Management 126: 239–254.

- Sleep, D. J. H., Drever, M. C. & Szuba, K. J. 2009. Potential Role of Spruce Budworm in Range-Wide Decline of Canada Warbler. Journal of Wildlife Management 73: 546–555. Available online: http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.2193/2008-216

- Cooper, J. M., Enns, K. A. & Shepard, M. G. 1997. Status of the Canada Warbler in British Columbia. B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Wildlife Branch. Wildlife Working Report No. WR-81, Victoria, B.C. 38 pp.

- Norton, M. R. & Hannon, S. J. 1997. Songbird response to partial-cut logging in the boreal mixedwood forest of Alberta. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 27: 44–53. Available online: http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/x96-149

- Odsen, S. G. 2015. Conserving Boreal Songbirds Using Variable Retention Forest Management. Master of Science. Dept. Renewable Resources, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB. 84 pp.

- Tittler, R., Hannon, S. J. & Norton, M. R. 2001. Residual tree retention ameliorates short-term effects of clear-cutting on some boreal songbirds. Ecological Applications 11: 1656–1666.

- Venier, L. A., Pearce, J. L., Fillman, D. R., McNicol, D. K. & Welsh, D. A. 2009. Effects of Spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem.)) outbreaks on boreal mixed-wood bird communities. Avian Conservation and Ecology 4: 3.

- COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Canada Warbler Wilsonia canadensis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa. vi + 35 pp. Available online: www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm)