Clark’s Nutcracker caches pine seeds for eating later, but they don’t relocate every last one. The nationally Endangered Whitebark Pine relies on this species’ forgotten caches for seed dispersal.

Clark’s Nutcracker

(Nucifraga columbiana)

Habitat Ecology

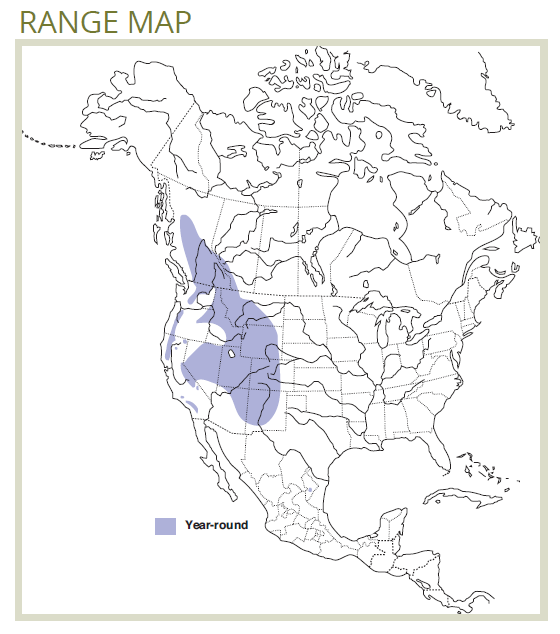

- Clark’s Nutcracker occupies semi-open montane and subalpine coniferous forests dominated by ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, limber pine, and/or whitebark pine.1

- It is a resident species that is found mainly in subalpine forests in the spring and summer, moving down to montane forests in the late autumn, although these movements are not consistent among all populations.1,2

- Clark’s Nutcracker is rarely found at altitudes higher than 2,600 m.1

- This species breeds as early as January, with peak breeding from early February to late May. This means that standard avoidance techniques may be ineffective for reducing incidental take.1

Response to Forest Management

- Clark’s Nutcracker is highly threatened by tree mortality and reduced cone production resulting from mountain pine beetle outbreaks and whitebark pine blister rust.3

- Fire suppression in the Rocky Mountains has made whitebark pine more vulnerable to these threats.1

- Recent clearcuts may be used for seed caching, as well as recent openings caused by burns.4

Stand-level Recommendations

- This species requires ≥10 ha whitebark pine stands with an average cone density of ≥1,000 cones/ha.5 The following actions are recommended where these stands, or stands nearly meeting these conditions, are identified:

- In collaboration with provincial land managers, prescribed burning at a location within 10 km of the stand can create habitat for caching.5

- Planting of rust-resistant whitebark pine seedlings in stands that approach but do not meet this threshold.5

- Thinning treatments targeting non-whitebark pine species, followed by prescribed burning, may create caching habitats. The effectiveness of this approach has been mixed and it should be undertaken with caution.6,7

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Maintenance or restoration of healthy populations of limber pine and whitebark pine are considered essential to maintaining Clark’s Nutcracker populations.8

- Whitebark pine restoration is recommended for locations adjacent to habitat mosaics that include Douglas fir, an alternative food source which may attract Clark’s Nutcracker.9

Knowledge Gaps

- Studies have mainly focused on Clark’s Nutcracker responses to whitebark pine restoration treatments, while responses to conventional harvests are unclear.

- Sensitivity to human disturbance is unknown during their winter nesting period.1 This knowledge gap has implications for avoiding incidental take and the unknown effectiveness of nest buffering.

References

- Tomback, D. F. 1998. Clark’s Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.331

- Lorenz, T. J. & Sullivan, K. A. 2009. Seasonal differences in space use by Clark’s nutcrackers in the Cascade Range. The Condor 111: 326–340. Available online: http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1525/cond.2009.080070

- Alberta Whitebark and Limber Pine Recovery Team. 2014. Alberta Limber Pine Recovery Plan 2014 – 2019. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, Alberta Species at Risk Recovery Plan No. 35, Edmonton, AB. 61 pp. Available online: http://www.whitebarkpine.ca/uploads/4/4/1/8/4418310/sar-limberpine-recov…

- McMurray, N. E. 2008. Nucifraga columbiana. in Fire Effects Information System [Online] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/animals/bird/nuco/all.html

- Mckinney, S. T., Fiedler, C. E. & Tomback, D. F. 2009. Invasive pathogen threatens bird-pine mutualism: implications for sustaining a high-elevation ecosystem. Ecological Applications 19: 597–607.

- Keane, R. E. & Parsons, R. A. 2010. Restoring whitebark pine forests of the northern Rocky Mountains, USA. Ecological Restoration 28: 56–70. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs_other/rmrs_2010_keane_r002.pdf

- Russell, R. E. et al. 2009. Modeling the effects of environmental disturbance on wildlife communities: avian responses to prescribed fire. Ecological Applications 19: 1253–1263. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1890/08-0910.1/abstract

- Blouin, F. 2006. The southern headwaters at risk project: a multi-species conservation strategy for the headwaters of the Oldman River. Volume 3: Landscape management – selection and recommendations. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 105, Edmonton, AB. iv + 34 pp.

- Schaming, T. D. 2016. Clark’s nutcracker breeding season space use and foraging behavior. PLoS ONE 11: 1–20. Available online: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0149116