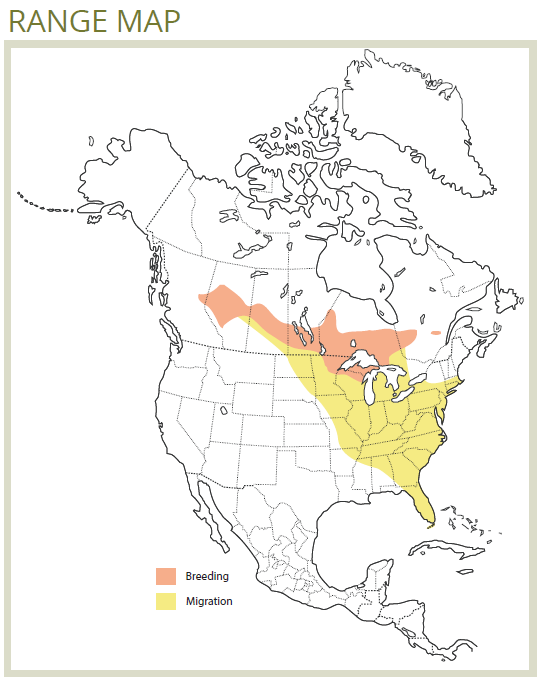

The Connecticut Warbler is less well-studied than other warblers due to its inconspicuous behavior. Alberta, Saskatchewan and BC represent the western edge of its breeding range.

Connecticut Warbler

(Oporornis agilis)

Habitat Ecology

- Connecticut Warblers are mainly found in deciduous forests and aspen-leading mixedwoods with a well-developed shrub layer (aspen, rose, beaked hazelnut, alder, willow, and fruiting shrubs).1,2 However, its habitat selection is highly variable across its range:

- It is also found at the edges of small meadows, wetter stands with high tamarack cover and low shrubs,1,2 and in eastern North America, muskegs and lowland conifer forests.3

- This species occupies a range of stand ages ranging from 0–10 years to mature and old (>76 years) aspen and mixedwood forests.4,5

- Its nest is built on or near the ground, often in thickets, clumps of vegetation, or at the base of a shrub.1

Response to Forest Management

- This species is more abundant in recently burned than recently harvested forest,6 and is more abundant in burned riparian forest than intact or partially-harvested riparian buffers.7

- In BC, the largest threats to Connecticut warbler include 1) herbicide application to reduce understory vegetation and deciduous regeneration and 2) logging of aspen stands.1

- Connecticut Warbler has shown mixed responses to retention harvesting. High retention (>20%) appears to have a negative effect, however lower retention levels (e.g., 10%) may benefit this species.8

- Regenerating clear-cut stands (i.e., no planned retention) are likely to contain Connecticut Warblers from 15–25 years postharvest.9

Stand-level Recommendations

- Managers should establish large retention patches (>5 ha) where possible, containing mature aspen or poplar and a well-developed shrub and herbaceous layer (particularly fruiting shrubs).5,10

- Retention harvesting (e.g., 10% retention in small, evenly distributed clumps) may be beneficial.8 Avoiding shrub and understory suppression using herbicides is also important for this species.1

- Mid-seral regenerating stands (15–25 years postharvest) may provide habitat for this species.9

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Forest management within the natural range of variation, including clearcuts, blocks containing low overall retention, blocks containing large (>5 ha) retention patches, burned forest, and larger areas of unharvested deciduous forest, is expected to benefit Connecticut Warblers on the landscape.

- Smaller patches and remnants have been shown to have greater benefits to this species when >5 ha and/or located closer to unharvested forest. Patches, remnants, and set-asides (preferably consistent with NRV patch sizes) are recommended with the following additional parameters:

- Pure aspen or mixedwood forest set-asides should contain old aspen (>40 years) and developed herbaceous and shrub layers.11

- Stands/remnants should be either very large OR smaller and located within 5 km of larger areas of high forest cover.5

- Stands/remnants located on flat sites or gentle south- or west-facing slopes may have additional habitat value.11

References

- Pitocchelli, J., Jones, J., Jones, D. & Bouchie, J. 2012. Connecticut Warbler (Oporornis agilis), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.320

- Hobson, K. A. & Bayne, E. M. 2000. Breeding bird communities in boreal forest of western Canada: Consequences of ‘unmixing’ the mixedwoods. The Condor 102: 759–769. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1370303

- Zlonis, E. J., Panci, H. G., Bednar, J. D., Hamady, M. & Niemi, G. J. 2017. Habitats and landscapes associated with bird species in a lowland conifer-dominated ecosystem. Avian Conservation & Ecology 12: 7.

- Schieck, J. & Song, S. J. 2006. Changes in bird communities throughout succession following fire and harvest in boreal forests of western North America: literature review and meta-analyses. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36: 1299–1318. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1139/x06-017

- Hobson, K. A. & Bayne, E. M. 2000. The effects of stand age on avian communities in aspen- dominated forests of central Saskatchewan, Canada. Forest Ecology and Management 136: 121–134. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00287-X

- Hobson, K. A. & Schieck, J. 1999. Changes in bird communities in boreal mixedwood forest: Harvest and wildfire effects over 30 years. Ecological Applications 9: 849–863.

- Kardynal, K. J., Hobson, K. A., Van Wilgenburg, S. L. & Morissette, J. L. 2009. Moving riparian management guidelines towards a natural disturbance model: An example using boreal riparian and shoreline forest bird communities. Forest Ecology and Management 257: 54–65.

- Tittler, R., Hannon, S. J. & Norton, M. R. 2001. Residual tree retention ameliorates short-term effects of clear-cutting on some boreal songbirds. Ecological Applications 11: 1656–1666.

- Leston, L., Bayne, E. & Schmiegelow, F. 2018. Long-term changes in boreal forest occupancy within regenerating harvest units. Forest Ecology and Management 421: 40–53. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.029

- Cooper, J. M. & Beauchesne, S. M. 2004. Bay-breasted Warbler. in Accounts and Measures for Managing Identified Wildlife (Version 2004) Biodiversity Branch, Identified Wildlife Management Strategy, Victoria, BC. Available online: http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/frpa/iwms/documents/Birds/b_baybreastedwarb…

- Cooper, J. M. & Beauchesne, S. 2004. Connecticut Warbler. in Accounts and Measures for Managing Identified Wildlife (Version 2004) Biodiversity Branch, Identified Wildlife Management Strategy, Victoria, BC.