Also known as a Whiskeyjack, the Gray Jay is an iconic Canadian species known for its low fear of humans. It is also an important nest predator in the boreal forest and may pose a threat to at-risk songbirds.

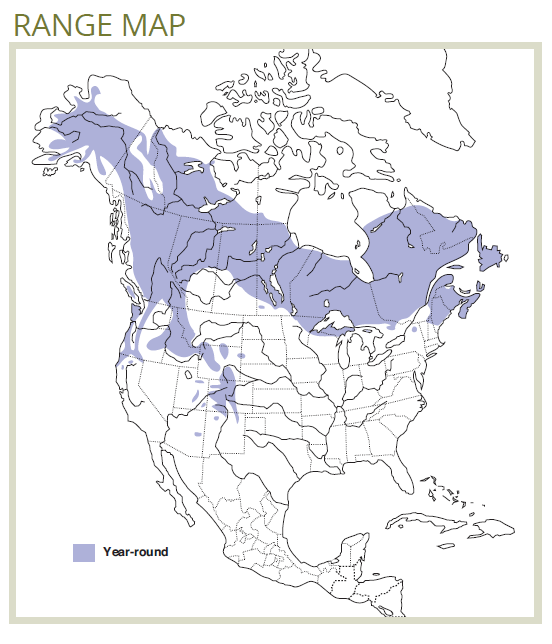

Gray Jay

(Perisoreus canadensis)

Habitat Ecology

- Gray Jays are mainly found in coniferous and mixed coniferous-deciduous forests, particularly spruce-leading stands. They are also abundant in black spruce and jack pine stands (Saskatchewan),1 Douglas fir and Engelmann spruce above 100m elevation (southern BC),2 open and semi-open woodlands, and near bogs.3

- There is some evidence of higher Gray Jay abundances at the boundaries between coniferous and deciduous forests.4

- This species is widespread across coniferous-leading forests including disturbed and fragmented areas. It is most common in old forests and is also found in burned stands containing snags.5

- The Gray Jay nests during late winter (beginning mid-March) and may be vulnerable to incidental take during winter logging.2

Response to Forest Management

- Gray Jays are rare or absent in large clear-cuts because they need trees for nesting and food caching.2

- Retention harvests with up to ~22% forest cover in 2–5 ha patches and riparian buffers supported fewer Gray Jays than unharvested forest, but substantially more than in clear-cuts.6

- This species has responded positively to thinning in Douglas-fir forests (~60% stem density removal)7 and selection cutting with 60–70% retention in lodgepole pine forests.8

- In Quebec, responses to forest edge in balsam fir forests suggest that heavily fragmented forest may provide high-value habitat for 20–30 years post-disturbance.9

Stand-level Recommendations

- High-intensity thinning and low-intensity selection cutting appear to benefit this species.7,9

- Retention harvesting is recommended over clear-cutting, leaving large retention patches containing coniferous trees for nesting and food caching.6

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Fragmented landscapes may attract Gray Jays, particularly to forest within 30 m of disturbance edges. This attraction may have unintended negative effects on nesting songbirds in the same area as Gray Jays are an important nest predator.9

- While this species will benefit from old coniferous stands (set-asides, remnants, etc.) on the landscape, its tolerance of harvesting other than clear-cutting suggests it is likely to be resilient to many landscapes managed under NRV and using harvest systems including retention, selection cutting, and thinning. It is also highly likely to benefit from old black spruce and tamarack forests, which may be well-represented on the passive land base.10

References

- Hobson, K. A. & Bayne, E. M. 2000. The effects of stand age on avian communities in aspen- dominated forests of central Saskatchewan, Canada. Forest Ecology and Management 136: 121–134. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00287-X

- Strickland, D. & Ouellet, H. R. 2011. Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis). in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/gryjay

- B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2017. Species Summary: Perisoreus canadensis. Minist. of Environment Available online: http://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/

- Sieving, K. E. & Willson, M. F. 1998. Nest predation and avian species diversity in northwestern forest understory. Ecology 79: 2391–2402.

- Hobson, K. A. & Schieck, J. 1999. Changes in bird communities in boreal mixedwood forest: Harvest and wildfire effects over 30 years. Ecological Applications 9: 849–863.

- Lance, A. N. & Phinney, M. 2001. Bird responses to partial retention timber harvesting in central interior British Columbia. Forest Ecology and Management 142: 267–280.

- Hagar, J. C., Howlin, S. & Ganio, L. 2004. Short-term response of songbirds to experimental thinning of young Douglas-fir forests in the Oregon Cascades. Forest Ecology and Management 199: 333–347.

- Waterhouse, M. J. & Armleder, H. M. 2007. Forest bird response to partial cutting on caribou winter range in west-central British Columbia. BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management 8: 75–90. Available online: http://www.forrex.org/publications/jem/ISS39/vol8_no1_art6.pdf

- Ibarzabal, J. & Desrochers, A. 2004. A nest predator’s view of a managed forest: Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) movement patterns in response to forest edges. The Auk 121: 162–169. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4090065

- ABMI. 2017. Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis). ABMI Species Website, version 4.1 Available online: http://species.abmi.ca/pages/species/birds/GrayJay.html