This owl is named for the way its plumage looks like that of a hawk. Active during the day, the Northern Hawk Owl likes to perch on top of the most prominent trees, making it easy to spot (and a favourite of birders).

Northern Hawk Owl

(Surnia ulula)

Habitat Ecology

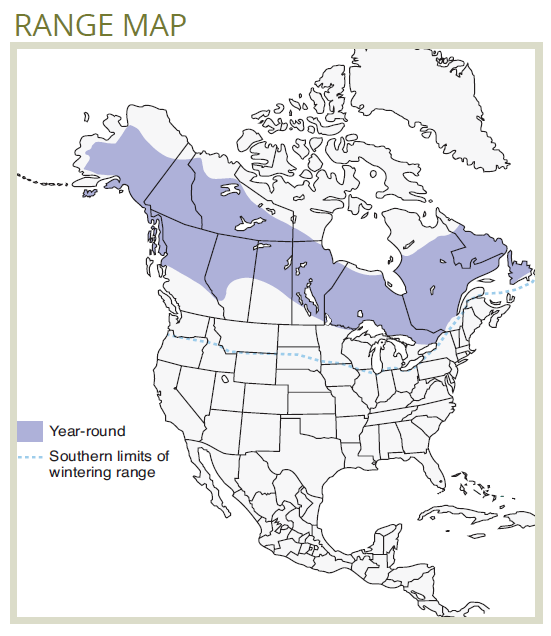

- The Northern Hawk Owl lives in the boreal forest year-round, where it is mainly found in moderately dense coniferous or mixedwood forests.1,2

- Key habitat features for this species include forest edges from which they hunt for small mammals,1 tall hunting perches (including residual trees, snags, or stumps within openings),2 and nest trees (see below).

- Northern Hawk Owls are often found near water, including riparian closed conifer forests.1 They are also found in burned forests, which typically provide hunting, perching, and nesting habitats.1,3

- This species nests in old Pileated Woodpecker and natural tree cavities. Hollow stubs,1 broken-topped snags,2 and aspen >35 cm dbh with signs of damage or decay4,5 are all potential nest trees.

Response to Forest Management

- The Northern Hawk Owl’s response to forest management in North America is not well-studied.

- Given this species’ habitat ecology, it is generally expected to be negatively impacted by very large (e.g., >100 ha) clearcuts that do not contain any retention.2

- In contrast, retention harvesting is expected to benefit Northern Hawk Owls by increasing prey populations, providing open areas for hunting, and maintaining nest trees and perches. These benefits are expected to last ~15 years postharvest.2

- Burned coniferous or mixed forests provide high-quality habitats, but rapid regeneration reduces habitat value after ~8 years in some regions.3

Stand-level Recommendations

- If the following features are maintained within harvest blocks, foraging habitat for Northern Hawk Owls is expected to increase:

- Tall perches (singly or in patches), especially trees without dense foliage and/or snags and in cutblocks >2 ha.1

- Existing or potential nest trees: trees, snags, or stumps with cavities, broken-topped snags, and aspen >35 cm dbh with damage or signs of decay (e.g., false tinder conks). Nest trees can be retained along edges and within patches.1,4,5

- Shrub suppression through silviculture in 11–15 year-old cutbocks may maintain foraging habitat value for longer.1

- During salvage logging, operators should retain patches containing large-diameter snags and trees/snags with visible cavities to reduce the negative effects of salvaging on nest availability.1,3

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Recently burned forests (2–8 years) may represent crucial habitat, especially at margins between coniferous and mixed/deciduous forests. These stands provide high-quality foraging habitat as well as nest trees.3 Retention harvests may provide similar value to this species on managed landscapes, but further research is required in North America to confirm this expectation.

- Unharvested riparian buffers and non-operable wet areas within coniferous or mixed forests, as well as areas containing stunted or scrubby spruce, may contribute to Northern Hawk Owl habitat on the landscape (studies are needed to confirm this).

References

- Duncan, J. R. & Duncan, P. A. 2014. Northern Hawk Owl (Surnia ulula), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.356

- Duncan, P. A. & Harris, W. C. 1997. Northern Hawk Owls (Surnia ulula caparoch) and forest management in North America: a review. Journal of Raptor Research 31: 187–190. Available online: https://sora.unm.edu/node/53606

- Hannah, K. C. & Hoyt, J. S. 2004. Northern hawk owls and recent burns: does burn age matter? Condor 106: 420–423. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1650/7342

- Cooke, H. A., Hannon, S. J. & Song, S. J. 2010. Conserving Old Forest Cavity Users in Aggregated Harvests with Structural Retention. Sustainable Forest Management Network, Edmonton, AB. 36 pp. Available online: https://doi.org/10.7939/R3JQ0SW3P

- Cooke, H. A. & Hannon, S. J. 2011. Do aggregated harvests with structural retention conserve the cavity web of old upland forest in the boreal plains? Forest Ecology and Management 261: 662–674. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.11.023