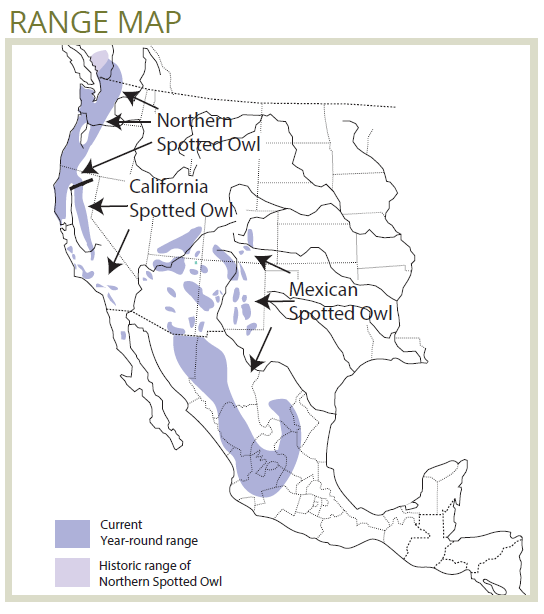

Wild Spotted Owl populations in British Columbia have fallen from about 1,000 (historical population estimate) to less than 30 individuals due to extensive habitat loss, fragmentation, and competition with Barred Owls. The province has undertaken several direct actions for their recovery including establishing extensive protected areas and a captive breeding program. Photo by US Fish & Wildlife Service

Northern Spotted Owl

(Strix occidentalis)

Rather than attempting to synthesize the many region-specific recommendations outlined in recovery and BMP documents, this species account provides a broad overview of recommended practices for improving habitat quality for Spotted Owls. Forest managers are referred to region-specific strategies, detailed species recovery plans/requirements, and/or provincial biologists within their Forest District for targeted guidance (see Resources section at the end of this account).

Habitat Ecology

- Spotted Owls reside in >100-year-old forests, and forest >140 years old is considered “superior.” Superior habitats are also conifer-dominated (preferably Douglas fir), multi-species stands with high stand complexity. Superior habitat is characterised by the following habitat features:1

- Canopy closure >70% provides thermal cover and protection from bad weather.1

- Broken-topped snags, cavities, mistletoe brooms, and in some cases abandoned raptor nests for nesting.1–3

- Vertical and horizontal structural diversity (i.e., 3 or more shrub/canopy layers) and perches at several heights.1,2,4

- Large-diameter trees (>75 cm dbh) and large snags, logs, and other downed woody material.2

- Patchy understory vegetation totalling >40% cover, over a quarter of which is shrubs.1

- Barred Owls have been expanding into the Spotted Owl’s range. Although closely related, the Barred Owl consistently out-competes Spotted Owls, and is thus considered a significant threat.2,5

Response to Forest Management

- Habitat loss, fragmentation, and replacement of old forests with dense, even-aged forests are among the primary threats to the Spotted Owl.2

- Fragmentation makes it more difficult for juvenile owls to safely disperse and establish new territories.2

- Spotted Owls appear to avoid hard habitat edges but favour diffuse edges created by low-severity fire.6

- Spotted Owl responses to stand thinning have been mixed; some studies have found negative effects of intensive thinning, while others have observed Spotted Owls in 10–50 year-old thinned and selectively harvested stands.5

- In California and Oregon, Spotted Owls were observed using variable retention harvest units, irregular shelterwoods, and seed-tree harvests. This response was attributed to high woodrat densities within these harvest blocks, but the authors cautioned that a different response was expected in Douglas fir/western hemlock forests where northern flying squirrel is a more important prey item.7

Stand-level Recommendations

- Within-block retention should be employed to promote the long-term structural diversity of harvested stands, including a combination of patches and dispersed retention,8 with an emphasis on large-diameter trees and snags with broken-tops, large horizontal branches, forks, cavities, mistletoe brooms, and evidence of decay.1,9

- The above features should also be retained during salvage logging following low- and medium-severity fires.5

- Large retention areas should be located in wetter areas and northern aspects, as these are more naturally resistant to fire.5

- See Blackburn and Godwin (2004) for retention targets within management zones for different BEC subzones.3

- Variable-density stand thinning may have short-term negative effects on northern flying squirrel abundances, but may provide long-term benefits to habitat quality and prey abundance (the oldest, largest trees and trees with deformities should be retained and snags should be created if not naturally available).5

Landscape-level Recommendations

- The creation of Wildlife Habitat Areas to protect known Spotted Owl habitat is the main tool recommended for protecting and recovering this highly endangered species. The recommended reserve size is 3,600 ha, of which 2,400 ha should be old forest.9

- In dry conifer forests that face a high risk of stand-replacing fires, there is cautious support for forest management that directly or indirectly promotes fire resistance.5

- Fuel reduction treatments are discouraged within 125 ha around nesting and roosting habitats.10

- Treatments may negatively impact local Spotted Owl habitat and/or nesting pairs in the short term.5,11

- Potential treatments include retention of fire- and drought-resistant tree species, reducing stand basal area around these tress, and thinning of dense young stands that result from fire suppression.5

- Natural fire refugia (wet areas, valley bottoms, perched water tables, etc.) may represent strategic areas for retention and reserves as they are more likely to resist future high-severity fire events.5

Resources

- Chutter, M. J. et al. 2004. Recovery strategy for the northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) in British Columbia. Prepared for the BC Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 74 pp. https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/rs_spotted_owl_caurina_1006_e.pdf

- Blackburn I, Godwin S. 2004. Spotted Owl, Strix occidentalis. Accounts and Measures for Managing Identified Wildlife – V. 2004. Biodiversity Branch, Identified Wildlife Management Strategy, Victoria, BC. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/natural-resource-policy-legislation/accounts-measures-for-managing-identified-wildlife/birds_spotted_owl.pdf

- BMPWG (Spotted Owl Best Management Practices Working Group). 2009. Best Management Practices For Managing Spotted Owl Habitat. Page Spotted Owl Management Plan 2 (Chilliwack Forest District, Squamish Forest District). BC Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Forests and Range. Available from http://bcwildfire.ca/ftp/DCK/external/!publish/SOMP/DOCUMENTS/SPOWBestManagementPractiesJul2009.pdf

References

- BMPWG (Spotted Owl Best Management Practices Working Group). 2009. Best Management Practices For Managing Spotted Owl Habitat. in Spotted Owl Management Plan 2 (Chilliwack Forest District, Squamish Forest District) BC Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Forests and Range. Available online: http://bcwildfire.ca/ftp/DCK/external/!publish/SOMP/DOCUMENTS/SPOWBestMa…. Accessed on August 30, 2013..

- COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Spotted Owl Strix occidentalis caurina Caurina subspecies. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa. vii + 48 pp.

- Blackburn, I. & Godwin, S. 2004. Status of the Northern Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) in British Columbia. B.C. Minist. Water, Land and Air Protection, Biodiversity Branch, Victoria, BC. Wildl. Bull. No. B-118.

- Gutiérrez, R. J., Franklin, A. B. & Lahaye, W. S. 1995. Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Revised recovery plan for the northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR. xvi + 258 pp. Available online: http://www.fws.gov/species/nso

- Comfort, E. J., Clark, D. A., Anthony, R. G., Bailey, J. & Betts, M. G. 2016. Quantifying edges as gradients at multiple scales improves habitat selection models for northern spotted owl. Landscape Ecology 31: 1227–1240. Springer Netherlands Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10980-015-0330-1

- Irwin, L. L., Rock, D. F. & Rock, S. C. 2013. Do northern spotted owls use harvested areas? Forest Ecology and Management 310: 1029–1035. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378112713002065

- Chutter, M. J. et al. 2004. Recovery strategy for the northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) in British Columbia. Prepared for the BC Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 74 pp.

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 9 Pacific and Yukon Region: Great Basin. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Delta, British Columbia. 105 pages + appendices.

- Tempel, D. J. et al. 2015. Evaluating short- and long-term impacts of fuels treatments and simulated wildfire on an old-forest species. Ecosphere 6: 1–19. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1890/ES15-00234.1/abstract

- Ganey, J. L., Wan, H. Y., Cushman, S. A. & Vojta, C. D. 2017. Conflicting perspectives on spotted owls, wildfire, and forest restoration. Fire Ecology 13: 1–20. Available online: https://www.frames.gov/catalog/25502