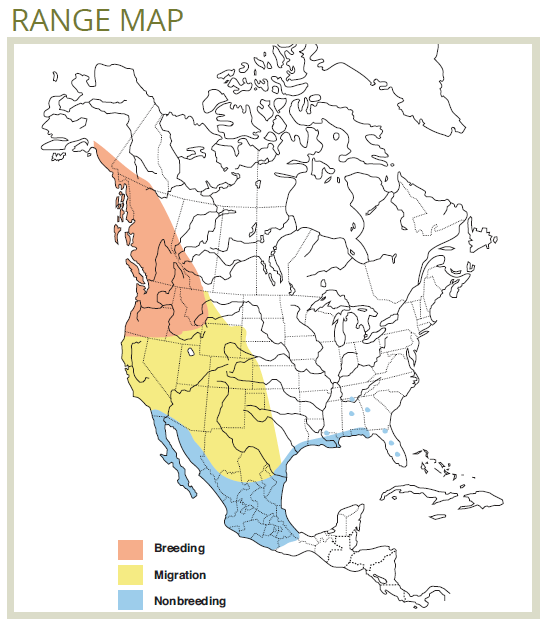

The Rufous Hummingbird is an incredible species that travels from Mexico and the Gulf States to the Pacific Northwest and as far north as Yukon and Alaska. And yet, it manages to return to the same site to nest each year.

Rufous Hummingbird

(Selasphorus rufus)

Habitat Ecology

- The Rufous Hummingbird feeds mainly on flower nectar, insects, and both the sap flowing from sapsucker wells and the insects that get caught in it.1,2

- This bird species is found in a wide range of habitats, and the common factor among them is the presence of flowering plants and shrubs.2 Habitats include:

- Dense second-growth and mature coniferous forests (primary breeding habitat).1

- Deciduous stands, riparian thickets, swamps, and meadows.1

- Young postfire and postharvest habitats with abundant shrubs.3

- Mature and old coniferous forests containing tree-fall gaps, natural openings, edges, and/or riparian habitats (i.e., openings where flowers grow) and old forest features including high structural diversity, high midstory cover, and lower canopy cover.2

- The Rufous Hummingbird mainly nests in conifers. They mostly nest in western redcedar and Douglas fir, and also nest in spruce, hemlock, pine, and fir trees. About 25% of nests are in deciduous species.1

Response to Forest Management

- Many studies have found a positive association between Rufous Hummingbird and clearcutting2,4–6 and narrower riparian buffers,7,8 and neutral to positive effects of thinning,4 selection harvesting,2 and patch retention.6

- However, other studies (primarily in the Washington Cascades) have found reduced numbers in old forests fragmented by clearcutting. Low numbers were also observed in young and mature stands, suggesting the above results should be interpreted with caution.2

Stand-level Recommendations

- Relatively young harvest blocks (with or without retention) with a well-developed shrub layer appear to be suitable habitat for this species. Foraging habitat for the Rufous Hummingbird may be improved by protecting and/or not suppressing understory shrubs during and after harvest.

- Retention patches containing preferred nest tree species (e.g., western redcedar and Douglas fir) may benefit Rufous Hummingbirds, however their direct use of retention patches for nesting has not been verified.

- Trees with visible sapsucker wells and high sap-yield species (e.g., paper birch) are recommended as anchor points for retention patches as they may increase food availability for Rufous Hummingbirds.

Landscape-level Recommendations

- While this species clearly benefits from early seral habitats containing flowering shrubs, the value of old forest, old forest features, and gap dynamics remains important on the landscape scale. NRV strategies promoting landscape heterogeneity, maintaining a mix of early- and late-successional forests (as well as natural disturbance dynamics including fire) will likely benefit the Rufous Hummingbird.

Knowledge Gaps

- Rufous Hummingbird populations have continued to decline despite increases in apparently suitable habitat (cutblocks and burned forest). While declines may be due to factors on wintering grounds and/or migration routes, reproductive studies comparing harvested, burned, and old forest habitats are recommended to determine whether harvest blocks are ecological traps for this species.1

References

- Healy, S. & Calder, W. A. 2006. Rufous Hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus). in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://birdsna.org./Species-Account/bna/species/rufhum

- B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2018. Species Summary: Selasphorus rufus. B.C. Minist. of Environment Available online: http://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/

- Hutto, R. L. & Young, J. S. 1999. Habitat relationships of landbirds in the Northern Region, USDA Forest Service. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-32. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, UT. 72 pp. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr032.pdf

- Hagar, J. C., Howlin, S. & Ganio, L. 2004. Short-term response of songbirds to experimental thinning of young Douglas-fir forests in the Oregon Cascades. Forest Ecology and Management 199: 333–347.

- Hutto, R. L., Hejl, S. J., Preston, C. R. & Finch, D. M. 1992. Effects of silvicultural treatments on forest birds in the Rocky Mountains: implications and management recommendations. Proceedings of a workshop held September 21-25, 1992, Estes Park, Colorado.

- Lance, A. N. & Phinney, M. 2001. Bird responses to partial retention timber harvesting in central interior British Columbia. Forest Ecology and Management 142: 267–280.

- Hagar, J. C. 1999. Influence of riparian buffer width on bird assemblages in western Oregon. The Journal of Wildlife Management 63: 484–496. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3802633

- Shirley, S. M. 2006. Movement of forest birds across river and clearcut edges of varying riparian buffer strip widths. Forest Ecology and Management 223: 190–199.