The Western Tanager is a handsome bird with a song that somewhat resembles a robin with a sore throat. Although it is common in open woodlands, it tends to stay in the shade, making it hard to spot.

Western Tanager

(Piranga ludoviciana)

Habitat Ecology

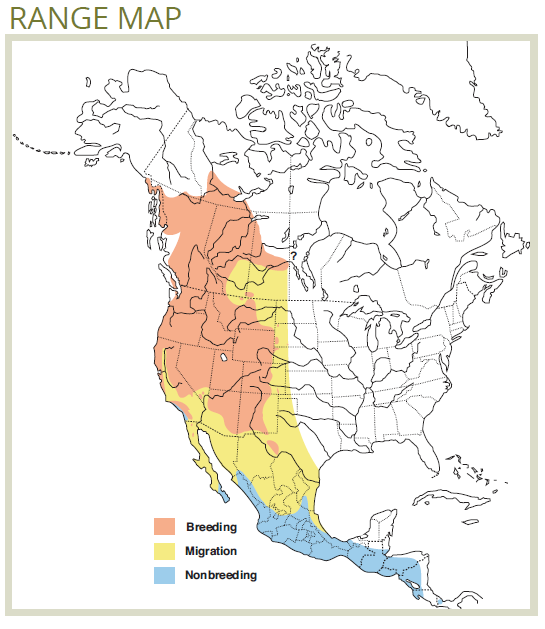

- The Western Tanager is found in a wide range of forest habitats west of Manitoba, but is mainly found in open coniferous, mixed coniferous, and mixed coniferous-deciduous woodlands.1

- This species is often found at forest edges of natural openings and transitions to aspen patches and second-growth harvest- and fire-origin stands.1,2

- They are associated with a high overstory canopy, large-diameter trees, and a coniferous component.1

- Western Tanager nest trees and habitat associations vary according to forest type:

- In boreal forests, they are associated with late-seral open coniferous or mixed coniferous-deciduous forest,1 particularly white spruce.3,4

- In ponderosa pine/Douglas fir/grand fir mixed conifer forests, they are associated with late-seral fire-origin forest and mid-seral forests originating from uneven-aged management and selection harvest.5

Response to Forest Management

- This species responds well to uneven-aged management including partial retention harvesting,6,7 but is rare or absent from regenerating clearcuts without residual trees (up to 33 years postharvest and possibly longer).6–8

- Thinning of Douglas fir stands increased Western Tanager numbers relative to unharvested stands.9,10

- Over 10 years, Western Tanagers had higher occupancy of wide (avg. 30 m) riparian buffers compared with narrow (avg. 13 m) buffers in Douglas fir/western hemlock/western red cedar forests.11

- Western Tanagers appear to be more sensitive to harvesting in aspen-dominated forests, where they prefer old unharvested forests over clearcuts and harvests with up to 40% retention.12,13

Stand-level Recommendations

- Within pure and mixed conifer forests, retention harvesting or thinning are recommended in lieu of clearcutting. The following habitat features are recommended for retention to increase within-stand complexity:

- Snags and large-diameter (e.g., >20 cm diameter) downed woody material1,5

- Deciduous species (e.g., paper birch, trembling aspen, black cottonwood),14 including large-diameter trees12

- Large-diameter coniferous canopy trees for nesting (e.g., white spruce or Douglas fir)1

- It is suggested that Western Tanagers breed in retention patches with preference given to larger patches, however patch size thresholds for successful breeding are not provided.1

Landscape-level Recommendations

- The Western Tanager’s association with high-contrast edges suggests they may be positively associated with landscape fragmentation. At the 300-ha scale in Douglas fir/western hemlock/western red alder forests, they have showed a preference for fragmented landscapes but were positively associated with the amount of late-seral forests.15

- Heterogenous landscapes subject to uneven-aged management, and containing high-contrast edges between stand types, late-seral forests containing conifer species (white spruce in boreal forests), and natural and man-made openings will likely benefit this species. However, high proportions of clearcuts with no retention are expected to have a negative effect.1,4

References

- Hudon, J. 1999. Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.432

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 6: Boreal Taiga Plains. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Edmonton, Alberta. 288 pp.

- Hobson, K. A. & Bayne, E. M. 2000. Breeding bird communities in boreal forest of western Canada: Consequences of ‘unmixing’ the mixedwoods. The Condor 102: 759–769. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1370303

- Mahon, C. L. et al. 2016. Community structure and niche characteristics of upland and lowland western boreal birds at multiple spatial scales. Forest Ecology and Management 361: 99–116. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.11.007

- Sallabanks, R., Haufler, J. B. & Mehl, C. A. 2006. Influence of forest vegetation structure on avian community composition in west-central Idaho. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34: 1079–1093. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4134319 Accessed:

- Lance, A. N. & Phinney, M. 2001. Bird responses to partial retention timber harvesting in central interior British Columbia. Forest Ecology and Management 142: 267–280.

- Schieck, J. & Song, S. J. 2006. Changes in bird communities throughout succession following fire and harvest in boreal forests of western North America: literature review and meta-analyses. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36: 1299–1318. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1139/x06-017

- Leston, L., Bayne, E. & Schmiegelow, F. 2018. Long-term changes in boreal forest occupancy within regenerating harvest units. Forest Ecology and Management 421: 40–53. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.029

- Hayes, J. P., Weikel, J. M. & Huso, M. M. P. 2003. Response of birds to thinning young Douglas-fir forests. Ecological Applications 13: 1222–1232. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/02-5068

- Hagar, J. C., Howlin, S. & Ganio, L. 2004. Short-term response of songbirds to experimental thinning of young Douglas-fir forests in the Oregon Cascades. Forest Ecology and Management 199: 333–347.

- Pearson, S. F., Giovanini, J., Jones, J. E. & Kroll, A. J. 2015. Breeding bird community continues to colonize riparian buffers ten years after harvest. PLoS ONE 10: e0143241. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143241

- Schieck, J., Stuart-Smith, K. & Norton, M. 2000. Bird communities are affected by amount and dispersion of vegetation retained in mixedwood boreal forest harvest areas. Forest Ecology and Management 126: 239–254.

- Norton, M. R. & Hannon, S. J. 1997. Songbird response to partial-cut logging in the boreal mixedwood forest of Alberta. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 27: 44–53. Available online: http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/x96-149

- Tobalske, B. W., Shearer, R. C. & Hutto, R. L. 1991. Bird populations in logged and unlogged western larch/Douglas-fir forest in northwestern Montana. Res. Pap. INT-GTR-442. US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Ogden, UT. 12 pp. Available online: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.goo…

- McGarigal, K. & McComb, W. C. 1995. Relationships between landscape structure and breeding birds in the Oregon Coast Range. Ecological Monographs 65: 235–260. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2937059