By Sarah Odsen

It’s been over a year since the Kenow Wildfire burned through Waterton Lakes National Park and surrounding forests, prompting evacuations and affecting the park’s ecology in profound ways. While the Landscapes in Motion team works to reconstruct past fire regimes, present-day wildfires like Kenow remind us of the wide-reaching effects these events have on the people living and working in forested areas. We spoke with Kim Pearson, an Ecosystem Scientist with Waterton Lakes National Park, about her experience and how Waterton’s forests have changed since Kenow.

Through the first week of September 2017, Kim Pearson and other Parks Canada staff were moving quickly. An Evacuation Alert had been announced for Waterton Lakes National Park, and they were preparing to relocate the essential pieces of Parks Canada’s operations to the nearby town of Pincher Creek. The urgency wasn’t just about making sure all visitors, staff and residents were evacuating safely—there was equipment to pack up and biological samples, the irreplaceable stuff of research, that had to be accounted for and transported away from the park. On Sept. 8th the Evacuation Order was put in place; only once Kim and others had helped sweep the Waterton Townsite did she turn her focus to preparing her home.

Wildfires are a natural process. Since it was not a matter of if but when a large fire would eventually take place within the park, Parks Canada had a wildfire management plan prepared for this scenario. Many years of planning had taken place for this eventuality.

… But it wasn’t possible to prepare for the emotional impact of the event that unfolded. It affected the landscape and community that Kim had been visiting since she was a child and that had been her home for 20 years. There was a lot of uncertainty about what would change because of the fire, but for Kim and the other residents of Waterton, it was clear that things were going to be different when they returned.

An unprecedented event

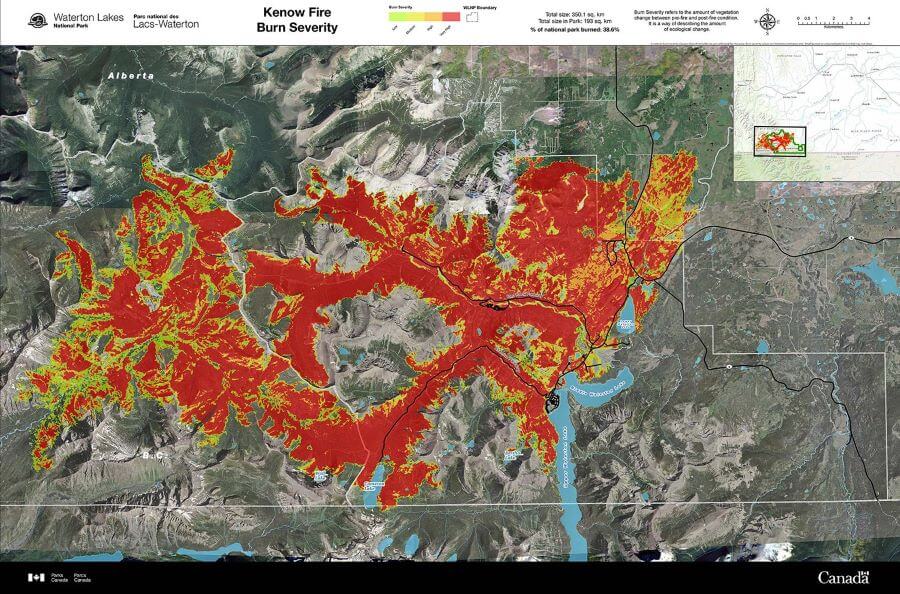

The Kenow Wildfire started in the Flathead region of B.C. and ultimately affected land in Waterton Lakes National Park, the province of Alberta, and two municipalities.

The scale and severity of the fire were greater than anything documented within the park since 1700, when the park’s fire history records begin. Eighty-eight percent of the burned area in the park was affected by “high” to “very high” severity, meaning that most or all of the organic matter was burned away by the fire. This uniformly high severity was exceptional for fires in this region. In much of the area, even the organic soil—that rich topsoil that plants grow best in—had burned away.

While it was burning, the wildfire’s behaviour was extreme due to a perfect storm of high winds and critically dry fuels. Normally, wildfires slow down at night and don’t move much until the heat of the day; this one shifted and accelerated into the park in the afternoon and continued to move quickly into nearby jurisdictions that night. Embers, those flaming pieces of vegetation that blow around and light smaller fires downwind, travelled as much as a kilometre ahead of the leading edge of the fire. There was at least one case where embers from Mount Crandell blew as far as 4 km, landing and starting a fire by the east side of Lower Waterton Lake.

Campgrounds, roads, trails… the effort to rebuild continues over a year later. Every aspect of the national park’s operations, planning, monitoring and management was affected in some way by the fire, not to mention effects to the local community and park infrastructure.

But not unprepared

The fire was massive and severe, but that does not mean the staff and residents of Waterton were caught unprepared. Parks Canada’s evacuation in response to the extreme wildfire was the result of careful planning and advance notice to ensure a safe and efficient process.

Months earlier, Parks Canada staff in Waterton conducted a tabletop exercise simulating a possible large-scale fire situation. They ran through what they would do, when, and how, identifying weaknesses and uncertainties in their preparedness and how to address them along the way. According to Kim, this exercise prompted several steps for preparedness which directly benefited evacuation efforts in 2017.

Growth, renewal, and hope

A year later, large parts of the landscape in Waterton are drastically different from what was there before the fire. Dead, blackened trees stand where old, dense forests once grew—yet the vibrant green of understory vegetation promises renewal. It might not all grow back the same, but the natural beauty of Waterton Lakes National Park remains.

Fire changes growing conditions in several ways. First, more sunlight reaches the forest floor because the canopy has burned away. Second, fire changes the chemistry of the soil in ways that can be better for some types of vegetation. And third, it becomes easier for some plants to access these soil nutrients when the insulating layer of duff is reduced or removed.

Even in the oldest forest, a suite of diverse vegetation is lying in wait for the right conditions to grow and reproduce, often at stunning speed. There are even species of fungi that spend most of their life cycles underground, sending up fruiting bodies (e.g., mushrooms or puffballs) only after a fire. In the park, some of these species will become visible for the first time in a couple of hundred years or more!

These conditions also help new lodgepole pine seedlings grow. This species is specially adapted so its cones open in the heat of the fire, allowing seedlings to grow in the bright sun and exposed soil of a burned forest. Despite some concerns that the high-intensity fire may have been so hot that it burned up the cones and seeds too, there are now large areas dotted with lodgepole pine seedlings that are thriving in the post-fire conditions.

Left: Lodgepole pine seedlings growing in the remnants of a red squirrel’s meal of lodgepole pine cones. Right: Lodgepole pine seedling growing next to a burned stump. Photos by K. Pearson (Parks Canada).

Not destroyed, but likely changed

The plants of Waterton Lakes National Park are growing back, but because of warmer, drier climate conditions the park is not expected to regenerate the same way it has in recent history. So far, lower elevations have seen the quickest rebound, with a lot of regrowth of grasses, wildflowers, and some shrubs. But at higher elevations, ecosystem renewal may take a different shape than what has been seen in the past—only time will tell.

In similar ecosystems in the United States, areas recovering from recent fires have experienced vegetation shifts that can be attributed at least in part to warmer and drier climate conditions. Similar changes may affect the renewal of Waterton’s ecosystems as well, and scientists will be watching closely to see how regeneration unfolds.

Unprecedented fire… unprecedented research!

In addition to the in-house research efforts by Parks Canada, 2018 is shaping up to be one of the busiest for research permits in the park’s history. Studies of vegetation growth and ecosystem succession will play an important role in understanding not only how this fire has affected Waterton, but how similarly large and severe fires may affect other Canadian landscapes.

Wildlife research will take advantage of monitoring programs in place before the fire, which puts researchers in a great position to study the effects of this fire on birds, bats, amphibians, large mammals, and invertebrates. Large fire events also have the potential to affect the hydrological cycle, and researchers will be looking at the hydrology and water quality of streams running through the park.

In an interesting twist, the fire has also exposed many archaeological and historical features and objects that had been hidden under the vegetation for decades, centuries, or even millennia! This past summer, Parks Canada archaeologists studying both Indigenous and European artifacts have been racing against time to catalogue as many of these features as possible before the regrowth obscures them once again.

Archaeological finds include artifacts like this broken base of a projectile point (arrowhead), which dates back to the Late Pre-Contact Period (300 years ago or more). Photo courtesy Parks Canada.

Looking ahead for Waterton

As Kim spent a sleepless night packing up valuables and checking on neighbours, watching the red glow of flames making their way over the mountain near her home, she was faced with uncertainty about the changes the fire would bring. In the year since the Kenow Wildfire, she and her colleagues have been working hard to understand the changes that have taken place on this landscape treasured by so many Albertans. As the landscape renews and grows back in ways both familiar and new, they are getting a glimpse into what may be in store for other landscapes that experience regrowth under a new and warmer climate.

Understanding how landscapes and fire shape each other

Landscapes in Motion is, at its heart, a project to understand how today’s landscapes were shaped by fires of the past, and what that might mean for the future. As we are seeing in Waterton, wildfire is not an endpoint for an ecosystem but rather a critical and necessary part of a cycle of disturbance and renewal. For Waterton Lakes National Park, this story is just beginning, and scientists, visitors and residents like Kim are watching closely to see where it goes.

Landscapes in Motion thanks Kim Pearson (Parks Canada) for her generosity in telling her story of what happened before, during, and after the Kenow Wildfire, and Parks Canada for permission to use their images. Any errors in recounting this story are the responsibility of the author.

Sonya Odsen is an Ecologist and Science Communicator with a background in boreal ecology and conservation. She is a regular writer for Landscapes in Motion and is part of the Outreach and Engagement Team for the project.

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.