By Sarah Nason

A recent study led by Landscapes in Motion collaborator Dr. Chris Stockdale shows that since the early 1900s, 25% of grasslands have been lost in a large area of Alberta’s Southern Rocky Mountains[1]. Our blog team sat down with Dr. Stockdale to discuss the implications of these findings, the exciting opportunities of oblique photography, and the connections between this research and the Landscapes in Motion project. Dr. Stockdale is currently a Fire Research Scientist with the Canadian Forest Service.

In 2006, Dr. Chris Stockdale learned about a database of historical photos of Canada’s Rockies dating all the way back to the early 1900s: the Mountain Legacy Project. Looking at the incredible comparisons between photos taken 100 years ago and ones repeated in the same location today, he knew there was an opportunity to do much more than compare them with the naked eye.

Back in the early 2000s, there was no way to actually quantify the amount of change between two photos. Some photos showed striking differences, while others appeared unchanged in the last 100 years.

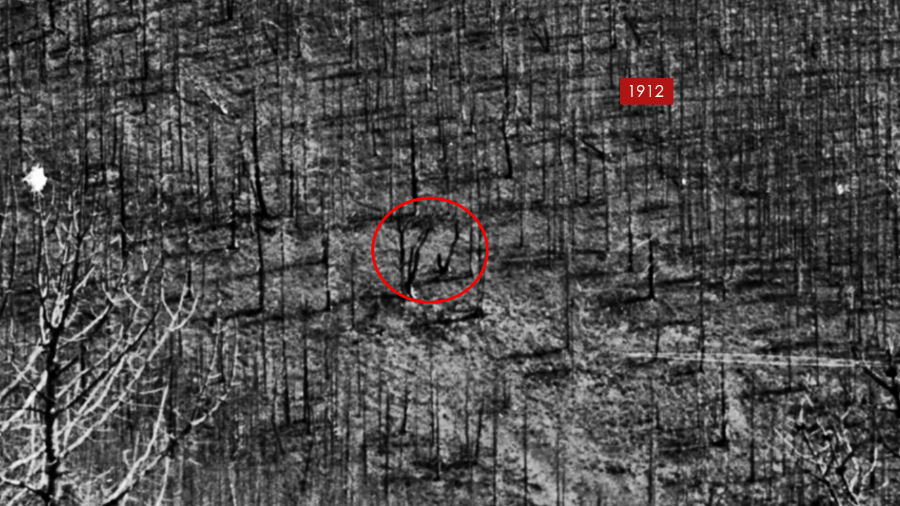

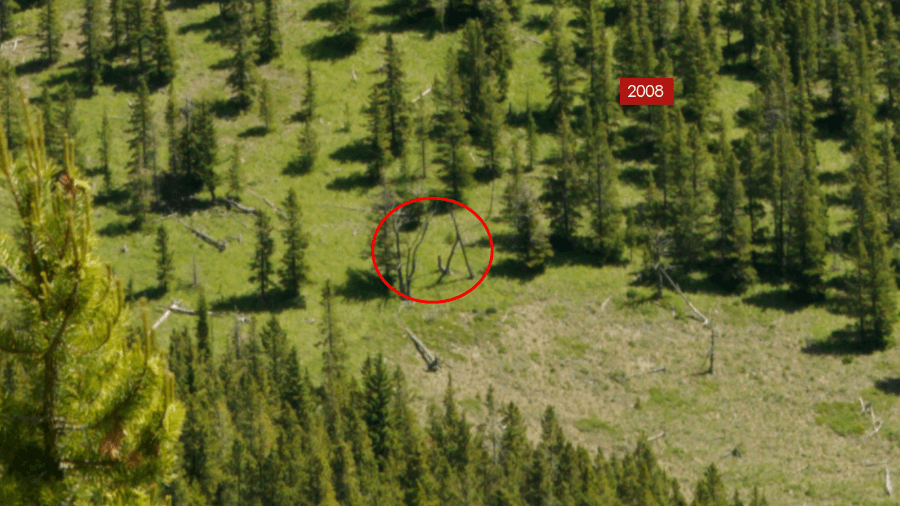

Repeat photographs reveal the complexity of landscape change: some parts of the landscape have changed dramatically while others have stayed much the same. When overlaying new photos on top of the old, Stockdale marveled at the snags circled above, which have remarkably stayed the same for nearly 100 years. Photographs courtesy of Chris Stockdale/Mountain Legacy Project.

“It became a long-standing obsession of mine,” Stockdale explains. “How could we use these photographs in a quantitative fashion?”

These landscape photos taken from the ground – called oblique photographs – had a lot of unlocked potential. Not only because they presented an opportunity to put concrete numbers on historical changes to the landscape, but also because they offered a window into a time period that researchers had not been able to study before.

Looking to the past to understand the present and future

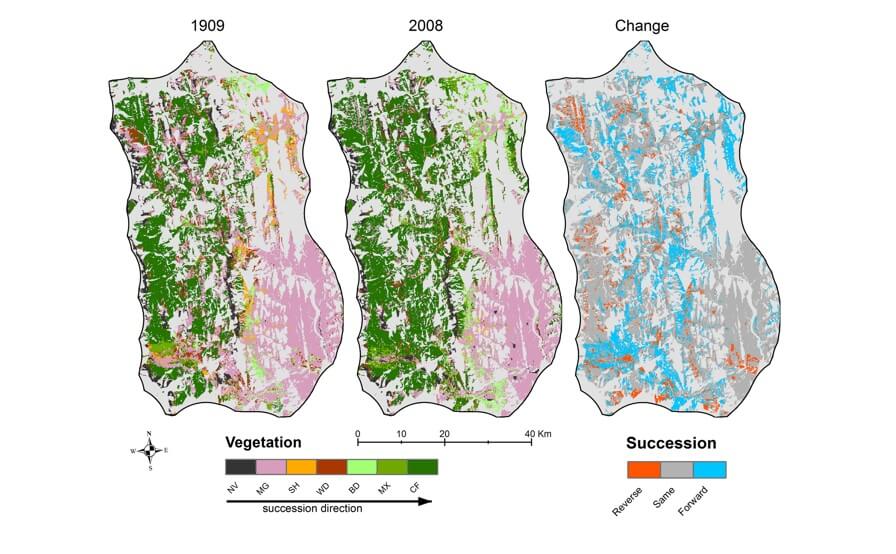

Using the Mountain Legacy photos, Stockdale and his team – Dr. Ellen Macdonald (University of Alberta) and the lead of the Landscapes in Motion oblique photography team, Dr. Eric Higgs (University of Victoria) – were recently able to look at the landscape of Alberta’s Southern Rockies 50 years farther back in time than was previously thought possible. In past studies, researchers made use of aerial photographs to look at landscape change, with the oldest aerial surveys only going back to 1949.

So, what is the value of going back an extra 50 years?

“1950 is well into the era when we started to suppress fires and when European settlement became dominant,” explains Stockdale. “At the turn of the century around 1900, that’s when the changes were starting to happen [in Western Canada].”

By looking farther back, researchers can start to understand the impacts that early European settlement, including policies aimed at reducing the number of wildfires[2], has had on the landscape. These impacts are critical for researchers to understand, because experts can only project the future based on their understanding of the past and present.

“Foundational historical knowledge is critical,” says Stockdale. “Models are built on known observations, so the more we have, the better we get.”

Growing forests and shrinking grasslands in Southern Alberta

When Stockdale and his team compared photos from the past to the present from 236 Mountain Legacy Project stations in the Southern Rockies of Alberta, they found an overall trend that might surprise some: while grasslands declined by 25%, various types of forest cover had increased by as much as 80%. Some researchers have called this phenomenon “an epidemic of trees.”

One of the biggest concerns related to losing grasslands is that a large number of endangered species in Canada rely on grasslands.

“By losing these grasslands at high and low elevations, we are losing critical habitat,” Stockdale explains. “And [forest encroachment] is not the only thing threatening grasslands – agriculture and human development are also there. Grasslands are getting pinched in on both sides.”

And it’s not only grassland-exclusive species that are likely to feel the impacts of grassland loss. Some species depend on both forested and open areas (called “borderland species”), often using forested areas for cover from predators and grasslands for sources of food.

What has caused this mass shift in vegetation? While it is hard to pinpoint one cause, there are many factors that have likely contributed to the changes. These include historic exclusion of fires in order to maintain forests, removal of large grazers like bison and elk, climate change, and conversion of grasslands for human development and agricultural land use. In particular, following European settlement policies and laws were implemented by the Canadian government to exclude Indigenous cultural burns from the landscape. These cultural burns played an important role in maintaining grasslands on the landscape.

Implications for wildfire risk and fire regimes

A landscape covered in more trees has implications beyond impacts on wildlife. This change on the landscape is also likely to affect wildfire risk – but not in the way you might expect.

“It increases the likelihood of high intensity fires that are harder to control, but not necessarily the number of fires that will occur,” Stockdale explains.

When conifer forests burn, they release more energy than grassland fires. This means that forest fires tend to be more intense, especially when large parts of the upper canopy burn (“crown fires”). But the risk of a wildfire starting and spreading depends on many other factors like wind, weather, and the “shielding effects” of other landscape features like water bodies[3]. In fact, wildfires can be more likely to spread to a larger area when they start as grassland fires.

“Fire moves more quickly through grasses, so the potential scale of fires on the historic landscape could spread wider and faster,” says Stockdale. “However, it is easier to stop a grass fire. The grassland fire would grow faster, but can be kept smaller than a crown fire.”

The implication of Stockdale and his team’s findings is therefore that fires may be more intense now compared to the past due to the type of vegetation being burned, but that the number of fires overall may not necessarily be more frequent.

However, researchers’ understanding of the historical frequency of fires is also something that is shifting.

“Looking at historic photographs, it’s readily apparent that there were massive, massive fires in 1910 that burned at high intensity,” Stockdale reflects. “But it’s not like there are huge pulses of fire and then nothing – there are lots of little creeping fires in between. That’s what creates a lot of ecological diversity on the landscape.”

Where to next?

For Landscapes in Motion, a big part of our team’s work is to understand more about those little creeping fires. How has the sustained activity of fire on the landscape in the past, at lower and more intermediate intensities, shaped the landscape that we see today?

Stockdale sees a lot of opportunities for oblique photography to play a bigger role in that type of work going forward, especially in combination with the information that can be gained by studying tree rings (dendrochronology).

“When dendrochronologists go [to the field] to look for fire information, they have to use aerial photography to determine where they think old fires might have happened,” he explains. “With another 50 years of a record here, you can see where fires just happened on the landscape and that can guide field sampling.”

Excitingly, Landscapes in Motion researchers have recently taken a first step towards combining our oblique photography and dendrochronology datasets. Experts on our teams collaborated to figure out where photos taken from Mountain Legacy stations overlap with the sites where tree rings have been sampled to study fire history. By bringing these two sources of information together, our teams will be able to include all the insights that come from the historical photographs to build an even more accurate picture of forests’ histories.

Oblique photography offers a wide variety of exciting opportunities for researchers looking at all different types of landscape change. Imagine being able to step onto a landscape from 100 years ago and figure out where a glacier used to be, where a stream used to flow, or even where a landslide happened.

As Stockdale explains, the opportunities are vast: “for anything you can see in a photograph, we now have the ability to go back to the birth of photography to see how the landscape has changed.”

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.

22-August-2019: An earlier version of this blog post did not clearly recognize Indigenous cultural burning as a one of the major influences on the landscape that historically maintained grasslands. The text has been updated to reflect the importance of this practice in shaping the landscape.

[1] Stockdale, C.A., Macdonald, E., & Higgs, E. (2019). Forest closure and encroachment at the grassland interface: a century‐scale analysis using oblique repeat photography. Ecosphere 10(6): e02774. DOI: 10.1002/ecs2.2774

[2] Murphy, P.J. 1985. History of Forest and Prairie Fire Control Policy in Alberta. Alberta Energy and Natural Resources, Edmonton, Alberta. http://albertaforesthistory.ca/docs/historic_docs/Murphy1985_20160924.pdf

[3] Stockdale, C., Barber, Q., Saxena, A., and Parisien, M.-A. 2019. Examining management scenarios to mitigate wildfire hazard to caribou conservation projects using burn probability modeling. Journal of Environmental Management 233: 238-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.12.035

Thumbnail photo for this post: burrowing owl by Ray Hennessy on Unsplash.