“Quick, three beers!” is the distinctive song of the Olive-sided Flycatcher. This nationally

Threatened bird hunts by swooping over clearings, meadows, or wetlands and catching insects mid-air.

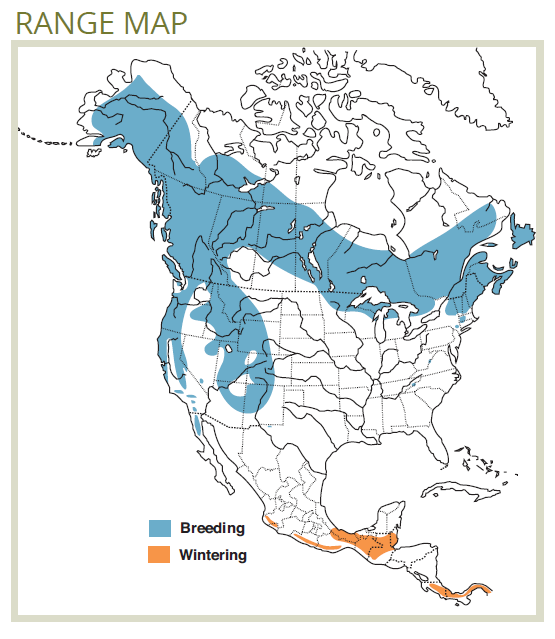

Olive-sided Flycatcher

(Contopus cooperi)

Habitat Ecology

- In western Canada, the Olive-sided Flycatcher is found in 0–30 year-old harvested stands and 0–10 year-old burned stands, provided they contain residual trees, and >125 year-old fire-origin mixedwood forests.1

- This species’ preferred habitat is old, open (<40% cover) coniferous forests or young burned stands, forest openings, and edges containing snags and live trees.2,3 Important habitat features for this species include:

- Tall, prominent perches (snags preferred to live trees).2,4

- Riparian areas, water bodies, swamps, bogs, and muskegs containing snags.2

- High-contrast edges between mature forest (used for nesting) and openings (used for hunting).5

Response to Forest Management

- Clearcutting without residuals, post-fire salvage logging, and herbicide and insecticide use are considered important threats to this species because they reduce forest diversity and structural complexity.6

- This species is attracted to young retention harvests, selection harvests, shelterwoods, thinned stands, and landscapes fragmented by clearcutting.1,2,7–9

- However, a small-scale study in the northern Rocky Mountains of the USA suggests that Olive-sided Flycatchers may preferentially nest in harvested stands with retention and have much lower nest success than in fire-origin openings due to increased nest predation.10

- Follow-up studies in western Canadian forests are strongly recommended to determine whether retention harvests are acting as ecological traps on these landscapes.

Stand-level Recommendations

- High densities of Olive-sided Flycatcher within harvest blocks containing residual spruce, fir, larch, and tall snags suggest that these features may be useful for improving habitat quality within harvested stands. The following harvest strategies and/or retention guidelines are expected to attract Olive-sided Flycatcher:4

- Coniferous residual trees of varying heights, singly or in small clumps, for perching (females prefer shorter trees for perching than males).

- Snags and trees exceeding the canopy height of retention patches and trees with reduced foliage at the top.

- Selection harvest within spruce, fir, and larch stands.

- However, if these stands are shown to lead to low Olive-sided Flycatcher nest success, alternative strategies will be needed to avoid unintended consequences (see Landscape-level Recommendations and Knowledge Gaps).4

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Coniferous areas which are patchy, recently burned, and contain wet areas are most likely to contain high densities of Olive-sided Flycatcher.6

- These types of forests can be maintained according to a region’s NRV, and may be well-represented within the passive landbase, particularly if salvage logging of burned stands can be deferred or avoided.11–13

- If retention harvests and other low-intensity harvests are shown to a) draw Olive-sided Flycatchers away from unharvested habitats and b) lead to reduced nest success, it may be more appropriate to avoid selective or retention harvesting on landscapes adjacent to the high-quality habitats described above for the 10 years following the burn.4

Knowledge Gaps

- Management implications for the Olive-sided Flycatcher are contingent on its reproductive success in harvested stands containing retention. It is critical to study this species’ reproductive output in retention harvests in western Canadian forests to determine whether these harvest treatments are having the opposite effect than is intended.

References

- Schieck, J. & Song, S. J. 2006. Changes in bird communities throughout succession following fire and harvest in boreal forests of western North America: literature review and meta-analyses. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36: 1299–1318. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1139/x06-017

- Altman, B. & Sallabanks, R. 2012. Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi), version 2.0. in The Birds of North America (Rodewald, P. G., ed.) Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.502

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 6: Boreal Taiga Plains. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Edmonton, Alberta. 288 pp.

- Robertson, B. A. 2012. Investigating targets of avian habitat management to eliminate an ecological trap. Avian Conservation and Ecology 7: 2. Available online: http://www.ace-eco.org/vol7/iss2/art2/

- Kline, J. D. et al. 2016. Evaluating carbon storage, timber harvest, and potential habitat possibilities for a western Cascades (US) forest landscape. Ecological Applications 26: 2044–2059. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/eap.1358

- Environment Canada. 2016. Recovery Strategy for Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vii + 52 pp.

- Beese, W. J. & Bryant, A. A. 1999. Effect of alternative silvicultural systems on vegetation and bird communities in coastal montane forests of British Columbia, Canada. Forest Ecology and Management 115: 231–242.

- Lance, A. N. & Phinney, M. 2001. Bird responses to partial retention timber harvesting in central interior British Columbia. Forest Ecology and Management 142: 267–280.

- Hagar, J. C., Howlin, S. & Ganio, L. 2004. Short-term response of songbirds to experimental thinning of young Douglas-fir forests in the Oregon Cascades. Forest Ecology and Management 199: 333–347.

- Robertson, B. A. & Hutto, R. L. 2007. Is Selectively Harvested Forest an Ecological Trap for Olive-Sided Flycatchers? American Ornithological Society 109: 109–121. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1650/0010-5422(2007)109[109:ISHFAE]2.0.CO;2

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 4 in Canada: Northwestern Interior Forest. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Whitehorse, Yukon. 138 pp. + appendices.

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 10 in Pacific and Yukon Region – Northern Rockies. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Delta, British Columbia. 109 pages + appendices.

- Environment Canada. 2013. Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 9 Pacific and Yukon Region: Great Basin. Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Delta, British Columbia. 105 pages + appendices.