By Sonya Odsen

The sky is dark, heavy, and silent as a summer storm creeps across the landscape. Suddenly… a flash.

For one brief moment, the forest is illuminated as an old tree erupts in a shower of sparks and flame. The rain continues to threaten but does not fall—instead, the wind picks up, fanning the flames until they catch on the next tree. And the next. And the next. A forest fire is born.

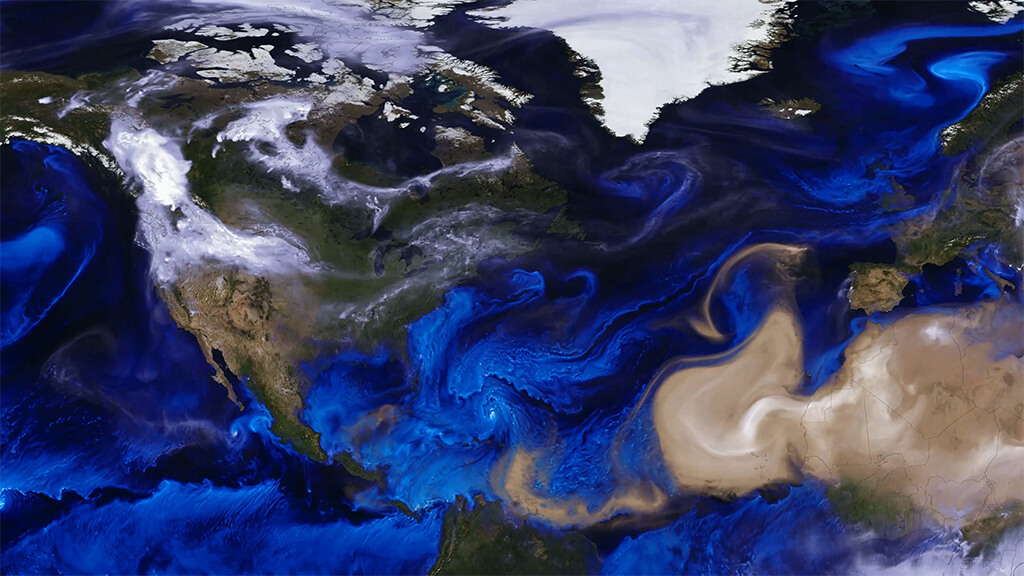

Over 1,200 wildfires covering 49,100 hectares (about 491 km²) have burned in Alberta in 2017, and nine of these are still active as of early November. This year’s fire season has felt like a lot, with the dramatic and rapid spread of the Kenow Mountain fire into Waterton Lakes National Park capping off the summer. But it’s actually been pretty mild, all things considered: the current five-year average for Alberta is slightly more fires (just over 1,400), burning a much larger total area of over 300,000 hectares on average (3,000 km², or a bit more than the size of Ottawa). Clearly, wildfire is a ubiquitous—if variable—force in Alberta.

What does this mean for the forest?

Well, that depends on a few things. Every fire encounters different conditions and is affected by different weather. Lightning may strike a tree growing on moist soil in a year with lots of rain, and just like trying to light a campfire using fresh damp wood, very little may come of it. Likewise, it might hit a tinder-dry tree in early spring after a winter with little snow, and grow suddenly out of control with help from strong winds.

In Canada, almost all fires are extinguished (naturally or through human efforts) before they grow to any substantial size. It is a small few that grow out of control, becoming the massive fire events that threaten communities and trigger air quality advisories across multiple provinces.

No two fires are the same

Depending on how hot and widely a fire burns, it affects forests differently.

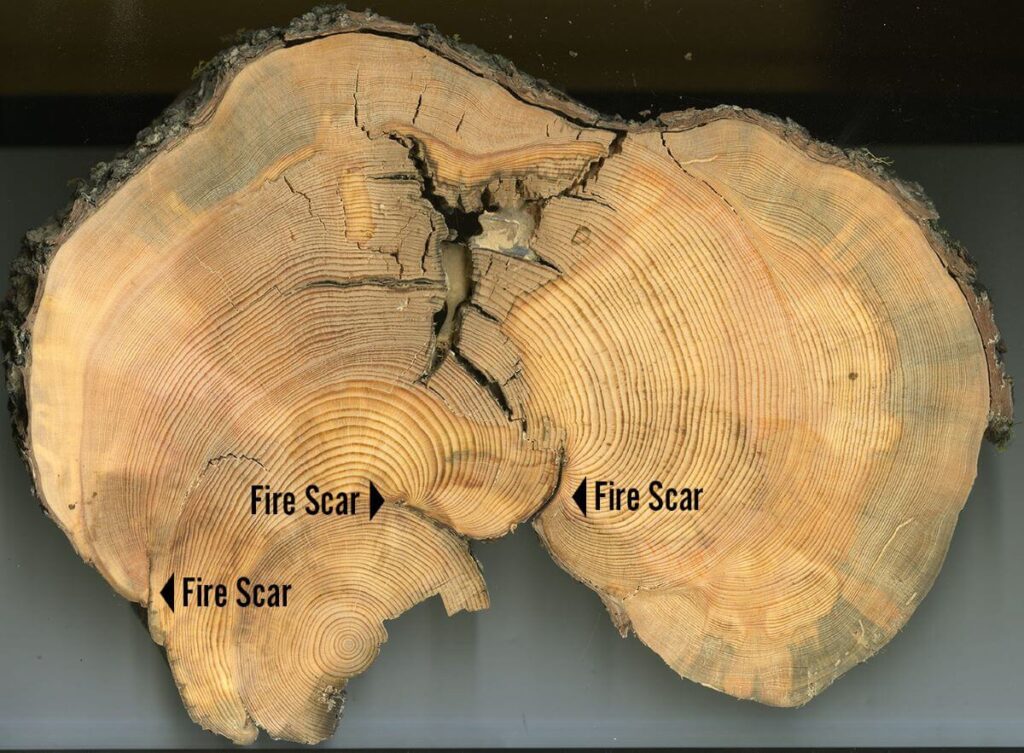

If lightning strikes a forest that is old, dry, and full of dead wood and litter, it might burn hot and fast. When a fire kills most or all of the trees where it burns, it is considered a “high-severity” fire.

One outcome of a high-severity fire is that it converts a dense, shady, cool forest into a warm, open, fertile environment. A high-severity fire burns up the thick layers of moss, lichen and litter on the ground, exposing and enriching the soil for new plants to sprout and take root. And there are many forest species that are waiting for exactly that opportunity.

Aspen trees, for example, have long networks of underground roots that will send up new shoots after a disturbance. Lodgepole pine cones have scales that are sealed shut, and the intense heat of a fire opens them and releases the seeds within to take hold on newly-exposed soil which is warm and fertile. Raspberry shrubs, fireweed, and other plants with seeds buried in the soil will pop up. What do these species have in common? They have trouble growing in the shady, cool, and nutrient-poor environments typical of mature forests.

The kind of forest that grows after a high-severity fire depends strongly on the original forest that burned. In the southern Rockies of Alberta, a mature lodgepole pine forest is often replaced by another lodgepole pine forest. The fire-adapted nature of their cones gives them a strong advantage over many other trees, and they rapidly grow to form a new, even, dense canopy.

However, not all fires burn this hot. Lower-severity fires can creep around for days or weeks at ground level, creating an entirely different environment. Although some trees may be injured by low-severity fires, most will survive. Some tree species have even evolved to have thick bark to help protect them from fire. The fire will also create a patchwork of dead trees, opening the door for tree and shrub species that rely on warm, sunny environments to grow. The result is a multi-layered forest community with a higher diversity of species, ages, and heights.

The combination of high- and low-severity fires (and everything in between) produces a patchwork of simple and complex forest stands across the landscape. This kind of landscape is more likely to be more resilient to future disturbances from fire, mountain pine beetle attack, and even climate change.

Cycles of rebirth

Forest fires are often associated with the death of a forest. Rather, whether it is a high-severity fire that consumes most of the trees and shrubs, or a low-severity fire that leaves most of the vegetation alive, fire is an integral part of a cycle of rebirth and rejuvenation in many Canadian forests. Fire enriches the soil and exposes it to sunlight, allowing new and unique forest communities to grow. The differences between high- and low-severity fires are critical to this cycle by creating a range of different community types, whether that’s across hundreds of hectares or in tiny patches.

Ultimately, fire is important because it shapes the forested landscape in regions like the southwest Rockies—and when we change how the forest burns, we change the forest itself.

Sonya Odsen is an Ecologist and Science Communicator with a background in boreal ecology and conservation. She is a regular writer for Landscapes in Motion and is part of the Outreach and Engagement Team for the project.