Throughout April and May this year, Alberta was still receiving plenty of snow. With no end in sight, there was an element of grim humour to the announcement that wildfire season had begun. The onset of the Chuckegg Creek fire near High Level, covering approximately 230,000 hectares as of May 31st, leaves us with no doubt that we are now firmly into wildfire season.

In both the present and the past, it is clear that humans have had a strong effect on why, where, and how forests burn. Recently, LIM researcher Dr. Cameron Naficy found some clues in the Southwestern Foothills showing that Indigenous cultural burning was likely a stronger influence on this landscape than previously documented in the academic literature. In this post, we share some context for the different ignition sources of Alberta wildfires and present a sneak peek into some of Dr. Naficy’s early findings.

Natural and cultural sources of ignition

Historically, wildfires have been a common natural process in many forests, including those in Southwestern Alberta. Whether these were severe stand-replacing events, low-severity surface fires, or some combination of the two, natural wildfires have shaped forested landscapes for centuries.

Before European colonization, there were two main points of ignition for wildfires. The first was lightning, which continues to account for about 35% of wildfires in Alberta today. The chance of lighting causing a fire depends on how dry a forest is, how much fuel is available to burn (e.g., dead wood and litter on the ground), and whether the immediate weather conditions fan the flames or douse them. Lightning strikes are not influenced by human presence, but rather by factors like storm patterns, forest type, and topography; this means they are just as likely to start a fire in a remote location, far from human development.

The other main point of ignition was traditional burning by Indigenous peoples. Fires were intentionally set to clear brushy forest, promote the growth of desired plants like berries, provide browse to important food species like moose, and create natural fireguards on the landscape. This tradition was practiced for many generations before Europeans arrived and started to reshape the landscape across much of North America, which included the implementation of policies and laws to suppress Indigenous cultural burning practices. Through long-term efforts to regain self-determination, Indigenous peoples continue to burn their land to this day.

New insights on landscape resilience emerge from historical cultural burns

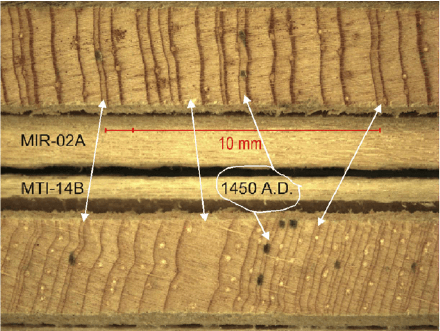

When Dr. Naficy and his team looked back into the history of wildfires in Alberta’s Southwestern Foothills using tree rings collected from the region, they uncovered an intriguing story about the history of fire and Indigenous peoples of this area. Lodgepole pine forests, which occupy much of the area, are considered in the scientific literature to burn infrequently and to be poorly adapted to frequent fire. But the tree rings tell a different story.

Dr. Naficy and his team found that lodgepole pine forests in the Foothills experienced relatively frequent historical fires. This pattern appeared in dozens of study sites throughout the montane zone of the Foothills and was consistent over at least the last few centuries. Not only that, but there are several clues suggesting that these frequent fires were strongly influenced by Indigenous cultural burning: lightning strikes are not common in the study area, meaning that human-caused ignition is a more likely explanation. On top of that, many fire scars on trees indicated that fires burned in spring and early summer – a pattern often associated with Indigenous fire use.

These findings emphasize that there is still much to learn about the history of North American landscapes. The lodgepole pine forests studied by Dr. Naficy and his team appear to be more resilient to frequent fires than previously assumed. These findings represent a shift in the research community’s understanding about how these forests respond to and interact with fire.

What other assumptions might we have about the landscape’s past that need to be challenged or tested? To fully understand the landscape’s past, there is a need for more targeted research like Dr. Naficy’s work, as well as stronger consideration of Indigenous knowledge, science, and history.

A new kind of ignition

These historical ignitions contrast with accidental wildfires, which are responsible for the other 65% of wildfires that burned in Alberta over the last decade.

In 2014, for example, 809 of the 1,414 recorded wildfires were ignited by sources other than lightning or prescribed burns. Of these, 372 fires were started by recreationists—mainly campers with unsafe campfires.[1] But accidental wildfires go beyond campfires, which tend to cause very small wildfire events. All-terrain vehicles with debris built up around exhaust pipes, brush pile burning by property owners, and industrial power lines and vehicles are all wildfire risks, to name a few.

Accidental wildfires are different from natural ignitions in many ways. First, they are most likely to occur where people are found—this means that fires are more concentrated in parts of Alberta where agriculture, forestry, and/or transportation (roads and railways) co-occur with forests.

Second, this proximity to people means that accidental wildfires are likely to be detected, reported, and extinguished much sooner. Unless the fire weather conditions are severe and the fire grows quickly out of control, most of these fires are put out before they reach a substantial size.

This contrasts with lightning, which accounts for a considerable portion of the area burned in Alberta. As you might imagine, a lightning strike in Northern Alberta, far from human activity and industrial infrastructure, may not be detected right away. It might also be a lower priority for fire crews if it does not pose a risk to communities or to economically valuable forests, especially if crews already have their hands full with fires that threaten cities, towns, and industrial centres.

Accidental wildfires are also very different from those intentionally ignited by Indigenous firekeepers. Traditional Indigenous burning techniques have been passed down through generations; fires are carefully located and timed to achieve the community’s objectives. This is a far stretch from an accidental ignition caused by an unattended campfire.

Changing ignitions, changing patterns

Following European colonization, there have been significant changes to where, when, and how large fires burn in Alberta’s forests. Understanding how the resulting forest patterns have changed on the landscape is a key objective of Landscapes in Motion. As our researchers continue to analyze the data that have been collected over the last two field seasons, we look forward to keeping you posted on the findings from this important work.

Want to learn more about fire safety?

Are you planning to head into the forest now that spring has sprung? If you want to learn more about fire safety and fire prevention, check out the following resources:

Wildfire prevention tips for OHV users

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.

[1] Data obtained from Alberta Historical Wildfire Database Tables 1999–2014.

Thumbnail photo for this post: view from Wasooch peak, Kananaskis, Alberta by Devin Lyster on Unsplash.