By Ceres Barros

[This post also appears on Ceres’ personal website. See it and her other work at ceresbarros.wordpress.com]

An important part of a researcher’s job is to learn more about what other scientists are doing in different institutions, fields, and ecosystems, and stay up-to-date on what they’re discovering. This year, Dr. Ceres Barros with the Landscapes in Motion modelling team identified a great opportunity to present her preliminary findings at a significant scientific conference in New Orleans. Once there, she had the chance to soak up new knowledge from fire ecologists from around North America. Dr. Barros gained some important new perspectives on her work with Landscapes in Motion and made some connections with fire ecologists from far beyond her home base at the University of British Columbia.

It was a meeting of ecologists like any other. Most of us were still wearing our field gear—ecologists are always ready for the field, and rarely ready for any formal event!—but the enthusiasm of meeting with colleagues and friends we haven’t seen for years was evident in many faces on the first day of the conference. We hugged, we talked about our current work, and got lost amidst the endless list of talks, workshops, and posters to choose from.

To top it all off, we got to experience it all in New Orleans, this year’s host city for the Ecological Society of America’s annual meeting! The city’s hot, humid air and ever-present jazz music were the perfect backdrop for our conversations. I was in for an exciting week and I couldn’t have been happier, regretting only that it never occurred to me to pack something warm enough for the air-conditioned conference hall!

One of the reasons why I chose to participate in this year’s meeting was the central theme: “Extreme events, ecosystem resilience and human well-being”. I knew I would be able to listen to many interesting talks on fire ecology that would give me a good overview of the ‘state of the art’ of the field, particularly in North America. I also hoped that many of these talks would touch on concepts of ecological resilience and stability, which describe how an ecosystem recovers after a disturbance and whether it experiences drastic changes, and which are among the primary drivers of my work.

I was not disappointed. I did attend several sessions focused on ecological stability and resilience, and I learned quite a bit about current research in fire ecology in North America. For instance, I learned that our fellow colleagues south of the border are increasingly concerned about how understory plant communities may affect diversity and/or tree growth after a fire. At the same time, many recognize the importance of fire for promoting ecosystem resilience and researchers are exploring the conditions under which fire can be used to maintain desirable ecosystem conditions.

What’s trending in fire ecology: role of the understory vegetation

There were two particularly interesting talks on the interplay between fire and understory communities that drew my attention.

The first was by PhD candidate Clark Richter, who shared the results from his research on post-fire regeneration in Sierra Nevada following the Power Fire in 2004. His work revealed that shrub cover is higher in patches that burned at higher severity (when tree mortality was close to 100%), but that there are fewer species of shrubs and trees that colonize these patches. This is partly because these patches have harsher conditions—soils become drier and more nutrient-poor following the loss of plant cover, and only the most hardy species can grow. In addition, many tree seedlings need light to germinate and grow, and they are unable to do so under the dense shrubs that regenerate faster in severely burned patches.

The second talk that stuck with me was by Dr. Jesse Miller. He pointed to similar results across several fires in California, but he further showed that variable-severity fires promoted higher levels of species diversity across the landscape than fires that burned mostly at high severity. He described these variable-severity fires—i.e., fires that killed less vegetation in some locations than in others— as having high ‘pyrodiversity’.

Although unsurprising, the results from these two talks confirmed my expectations that shrubs might outcompete trees in places where both trees and shrubs can colonize severely burned patches. They also confirmed for me the importance of mixed-severity fire regimes for maintaining landscape-wide plant diversity. Finally, they show that further increases in fire size and severity will compromise forest regeneration in many parts of the U.S. and quite likely Canada too.

For these and other reasons, fire ecologists are advocating more and more for the use of fire to promote ecosystem resilience. The talks by Emma Williams and Dr. Sharon Hermann presented the results of important field experiments that simulated different fire regimes using prescribed burning, then evaluated forest regeneration under these treatments. On the one hand, prescribed burning generally helped trees cope with drier conditions that typically follow fire, unless they had been exposed to drought before the fires. On the other hand, prescribed burning had no effect on the growth of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), an important species for the logging industry in the American state of Georgia. Finally, I was impressed to learn that researchers are testing the use of fire to control invasive species and/or less desired species.

Fresh eyes on my work

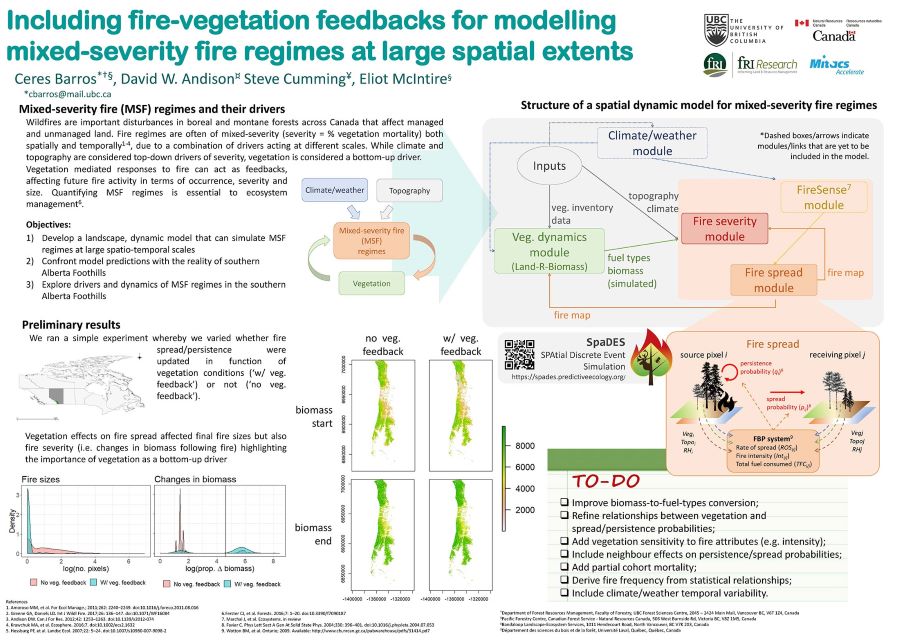

The other reason why I attended the ESA this year was to hear feedback on my own work. With my work fitting so well with the conference theme, I was eager to discuss it with other researchers and hear their thoughts and suggestions about the models I am developing.

I was extremely happy when other researchers in my field came around to have a look at my poster and discuss it with me. By then I already had a good idea of the direction fire research is taking in the U.S., so I was not surprised to hear some of them noting that my models may be biased if we don’t consider understory plant (e.g., shrub) recovery after a fire and how it influences tree regeneration.

At this point it is hard to foresee whether we’ll be able to take these aspects into account in our models, but we must not forget that they probably are important for ecosystem dynamics even in Canada. Either way, Landscapes in Motion is paving the way for more complex models of fire dynamics so that future researchers will be able to account for other forest components including not only understory species, but also pest and disease dynamics.

Our poster entitled “Including fire-vegetation feedbacks for modelling mixed-severity fire regimes at large spatial scales”. Despite being situated away from the main flow of people, many researchers in fire ecology and beyond came to see it and discuss with me. Photo by C. Barros.

I can’t say that the ESA meeting has significantly changed the plans I had for my work, but it surely consolidated my ideas. For one, I will keep in mind that my models may have some bias towards favouring tree regeneration because they do not account for shrub growth. Also, it will be interesting to assess landscape-wide diversity under different levels of fire severity and relate that to forest resilience to changing fire regimes. Finally, it was gratifying to hear my colleagues say that the work we are developing under Landscapes in Motion is very timely and everyone was looking forward to seeing more of the model!

All in all, it was a productive meeting in a vibrant and diverse city, and I came back to Victoria motivated and filled with eagerness to continue the development of our model!

Ceres Barros is a Post-Doctoral Fellow working with the Modelling Team of Landscapes in Motion. She also blogs on her website, and can be followed on Twitter (@CeresBarros).

Every member of our team sees the world a little bit differently, which is one of the strengths of this project. Each blog posted to the Landscapes in Motion website represents the personal experiences, perspectives, and opinions of the author(s) and not of the team, project, or Healthy Landscapes Program.