Ben Williamson

In January 2018, the Grizzly Bear Program started a new project that took us into new territory. The actual science is right in our wheelhouse. It’s about bear use on a working landscape, and it deploys methods that the team has used and refined over many field seasons: barbed wire, scent lures, and DNA. We’ve used these techniques to study the effects of things like forestry, oil and gas development, and roads. But last year, Grizzly Bear Program lead Gord Stenhouse noticed a scientific competition to, and saw an opportunity to take our research of grizzly bear co-existence on a working landscape and extend it to quarry mining. The goal of the competition, called the Quarry Life Award, is to improve the environmental performance of cement quarries. We partnered with Heidelberg Cement, which has a quarry less than an hour south of our offices in Hinton.

The other new element for the program was to hire local high school students for the field crew. This was a remarkable win-win: not only was this a great opportunity for students to get experience doing real conservation biology, but it made a lot of logistical sense for the project. The competition’s timeline is very compact (more on this later!), which meant that we had to get rolling before university and college students—our usual summer field recruits—would be done their winter semester. The relatively small study area and close proximity to Hinton meant that the amount of field work would fit comfortably on weekends; not enough to entice someone from out of town, but perfect for motivated high school students looking for a unique part-time job.

Off to the mine

On April 10, the team of Morgan, Bryce, Adam, and Hunter, led by Grizzly Bear Program biologists Anja Sorensen, Karen Graham, and Isobel Phoebus, set off for the Lehigh Cement Quarry near Cadomin for their first day of field work. Nestled up in the front ranges of the Rockies, the terrain was quite steep and still snowbound. Undaunted, they pushed through the deep snow drifts and picked out the most promising sites. They dug out an area the size of a big driveway and set up a sampling site.

This barbed wire approach is really the gold standard for getting information about grizzly bear presence in an area in a non-invasive way. The team first builds up a pile of branches and moss and douses it with a scent lure. We won’t get into all the herbs and spices, but suffice it to say that it smells absolutely disgusting to us, but seems to be extremely interesting to predators. Then, at about knee height, they stapled a strand of barbed wire to trees to make a corral around the pile. The idea is simple. Curious bears that want to check out the stench have no choice but to leave a tuft of hair on the barb as they climb over or under the wire. When the crew returns, they can bag the hair and send to the lab for DNA analysis. As a final step, they set up a trail camera pointed at the site to get a sense of other visitors that might not leave hair samples.

Off to the races

Grizzly Bear Program staff and the students set up two sites the first day, and two more on their next visit. Over the next eight weeks, they returned to the quarry every second weekend to collect hair samples, refresh the scent lure, and download the pictures that the camera traps snapped. During this sampling period, quarry employees also pitched in by collecting any bear scat samples they located during their daily travels around the site. By early June, the field work wrapped up, the hair snag sites were decommissioned, and the hair and scat samples were speeding off to the labs.

The timing was perfect. The project had to be done and dusted with a final report submitted to the competition judges by the end of September. Even with the genetics labs generously agreeing to expedite the DNA work, it was always going to be a photo finish, so the crew had to make their final sampling visit in early June. Meanwhile, the Grizzly Bear Program was shifting up the gears. They had hired 23 post-secondary students for the massive summer operations that would deploy the quarry methods across three vast areas of Alberta wilderness, and Sorensen and Phoebus were needed to each lead one of those battalions. The high school students too, were finishing exams and making plans. On their last day in the field, the crew showed an international panel of Quarry Life Award judges the sites at the mine before taking down the last string of barbed wire.

The now ex-high school students said their farewells as the summer swept the rest of the Grizzly Bear Program off to the wildlands. Through all the planning and improvisation, the helicopter rides and stuck trucks, the general organized chaos of not one, but three simultaneous major population surveys, which Stenhouse compares to military exercises, the hair samples were quietly sitting in a fridge in Nelson BC. The lab techs at Wildlife Genetics International extracted DNA from the follicles at the base of the grizzly bear hair and examined each one for a couple dozen markers that unlock a wealth of information about the bears. Meanwhile, scat samples were examined to the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research laboratory in Svanhold, Norway, where technicians are world renowned for their expertise in extracting DNA from bear scat. The bears’ sex, the number of individuals who visited the limestone quarry, whether they had been detected previously by one of our other surveys around Alberta, and even their familial relationships can all be determined from the DNA within those hair and scat samples.

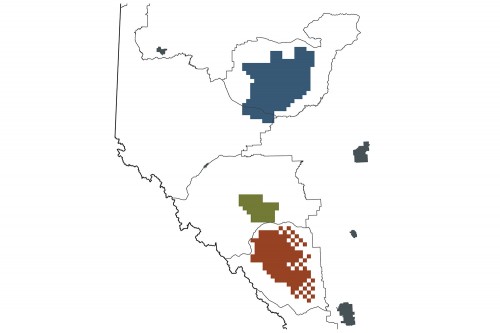

Three summer population inventories: Swan Hills in blue, Pembina in green, and Clearwarter in red. The quarry survey would be a smaller area to the west of Pembina.

Off to Dallas

By September, the crews had dispersed to universities, colleges, and other jobs across the country, including one quarry crew member who has started studying environmental sciences at the University of Alberta. About that time, the results came back from the labs, and the race was on to interpret the data and write the report before judging closed.

Those lab results revealed some fascinating findings! Using two genetic sampling approaches, six unique bears were detected on the quarry property; four males and two females. When comparing these genetic signatures to the Grizzly Bear Program’s long term datasets, we were able to recognize five of these individuals from previous research, including one bear translocated from southern Alberta by wildlife managers many years ago. By incorporating the Quarry Life Project results with 18 years of genetic sampling and collar tracking data collected by the Grizzly Bear Program, we were able to explore long term survival data, familial relationships and productivity within this ecosystem of which Lehigh Cement is a part.

The competition splits the projects into research and community streams. Our project was in the “habitat and species” category of the research stream, and so we were evaluated on how well we had “increased the scientific knowledge about biodiversity in mining sites to improve management actions at the quarry level.” We were feeling pretty good about that. We had done the first ever survey of grizzly bears on an active quarry in Alberta, using world class methods and engaged a local crew of students and mine employees in conservation of a threatened species.

On October 12, a vice president from Lehigh Hanson, which sponsors the competition, wrote to tell us that they agreed. A crew of four high schoolers in Hinton, Alberta, had won first place in the North American section. The student’s prize money will go towards their tuition, and Lehigh booked flights to the award dinner in Dallas. Unfortunately, the dinner on November 8 is smack in the middle of midterm exams for the students, so they were unable to accompany Stenhouse, Phoebus, and Sorensen. The project remains in the running for the international awards.